Travel

Search

THE INCAS MEET CHARLES DARWIN: MACHU PICCHU AND THE GALAPAGOS |

|

Harlan Hague |

Any time I have built up travel expectations sky-high, I prepare myself for disappointment. Such was the case as I boarded the plane in Miami one April. I was part of a group of eighteen that I had put together, and we were beginning a two-week trip that would include Machu Picchu and the Galapagos. The two destinations had been high on my travel priorities for years, and I had decided to combine them in one glorious adventure.

I was not disappointed. The Galapagos was as I expected, and Machu Picchu was pure magic. And these two destinations were only the beginning. There was considerably more to Peru and Ecuador.We flew into Lima and transferred to the Hotel Crillon for the night. My wife had a surprise when she opened her suitcase. In the mesh pocket inside the bag, she found a bottle of French lotion. Now, we've had things taken from our bags during transit, but never things put into our bags. An ominous beginning. The box had been opened, but apparently not the bottle. I encouraged her to toss it--no telling what mysterious substance was suspended in the solution--but she would have none of that.

Lima was but a way-station for us, and we left for Cuzco early the next morning. I regretted that we had not come a couple of days early, as some members of our group had done. They were much impressed with the Gold Museum and other attractions of Lima.

We had originally been booked on Aero Peru, but that airline went belly up in time for us to be rebooked on Aerocontinente before our departure from the U.S. The check-in at Aerocontinente was infuriating. It was as if they had never checked in a group before. There seemed to be plenty of personnel. They pondered, conferred, scratched their heads, and after an hour's delay finally began checking in our group. Ver-r-r-r-ry slowly. It would have been considerably faster if I had had members of the group check in individually.

Arriving in Cuzco, we met Raul, our Peruvian guide, boarded our bus and immediately

began our tour of the Urubamba Valley, the Sacred Valley of the Incas. Big mistake. We had

originally been scheduled to spend the remainder of the day at our Cuzco hotel, taking it

easy and adjusting to the altitude of over 11,000'. Most of us were from coastal

areas--the altitude at my home is 12'--and needed the adjustment. Our itinerary was inexplicably changed, and the kick-back time was

eliminated. Symptoms of altitude sickness began to appear that same evening.

needed the adjustment. Our itinerary was inexplicably changed, and the kick-back time was

eliminated. Symptoms of altitude sickness began to appear that same evening.

Leaving the Cuzco airport, our bus took us to Pisac, site of an important Inca fortress, where we visited the market. The goods and prices were attractive. My wife bought a chess set at the first stall she saw. We bought cloth holders for the ubiquitous plastic water bottles. We were already finding that the advice to drink lots of water in the warm, dry climate was wise. My wife was delighted with her purchase of a seventeenth-century Spanish coin. Members of our group began the process of loading up on colorful caps and hats, bags, purses, masks, wall hangings, and more, which would continue every time we encountered vendors. Children and women offered their products in a sweet, plaintive tone, not at all aggressive.

Continuing westward through the Urubamba Valley, we stopped at Inca ruins and had a

picnic lunch at a hillside site which had a spectacular view  of

the valley below. Inca terraces, dating from about the thirteenth century, fanned out from

one side of the site. Eight or ten children and women in traditional dress sat quietly

nearby as we ate our lunch. When they saw that we were finished, they came over, eager to

pose. We took pictures, and they sang for us. We thanked them and gave them some coins. We

found Peruvians everywhere polite and friendly.

of

the valley below. Inca terraces, dating from about the thirteenth century, fanned out from

one side of the site. Eight or ten children and women in traditional dress sat quietly

nearby as we ate our lunch. When they saw that we were finished, they came over, eager to

pose. We took pictures, and they sang for us. We thanked them and gave them some coins. We

found Peruvians everywhere polite and friendly.

In late afternoon, we drove into Ollantaytambo, a village that was old before the Spaniards arrived in the early sixteenth century. At the end of the town, a huge Inca complex of palaces and temples rises from the valley floor up the hillside. The structure served many purposes, religious, agricultural, social and administrative, as well as military. In anticipation of the arrival of the Spanish invaders, Inca leaders diverted the flow of a river into holding basins. When the Spaniards appeared on the plain before the fortress, the canals were opened, flooding the plain and routing the Spanish.

With darkness approaching, we had no time for the village of Ollantaytambo, though its narrow, cobblestoned streets and small plazas invited exploration. Another time.

We drove back down the valley to our hotel in Yucay. The Posada del Libertador is a hacienda style structure with a pretty, central courtyard and lots of rustic, local charm. Recommended.

We had our first mate de coca here. The coca tea had been recommended to us as an antidote to the symptoms of altitude sickness. Refreshing and perhaps effective. We were cautioned not to take any coca leaves home with us. The leaves are also the basis for cocaine. They have not been officially welcome in the United States since a well-known soft drink company experimented with them as an ingredient.

Next morning, after a refreshing breakfast of rolls, slices of papaya and other fruits,

juices and tea, we set out toward Cuzco. We stopped at a number of Inca sites en route and

ended at the magnificent Sacsayhuaman (think "sexy woman") on a

plateau overlooking the tiled roofs of Cuzco. This fortress with its massive,

delicately-shaped stones weighing as much as 125 tons each, is the best example of the

architectural skills of Inca builders. How the Incas moved the monster stones that make up

the double zig-zag wall, then shaped them so that they mesh tightly without the use of

mortar defies explanation. Most of the other structures of the complex had been built of

smaller stone, and they were reduced to their foundations by Spanish builders in Cuzco.

Sacsayhuaman is a must-see.

Sacsayhuaman (think "sexy woman") on a

plateau overlooking the tiled roofs of Cuzco. This fortress with its massive,

delicately-shaped stones weighing as much as 125 tons each, is the best example of the

architectural skills of Inca builders. How the Incas moved the monster stones that make up

the double zig-zag wall, then shaped them so that they mesh tightly without the use of

mortar defies explanation. Most of the other structures of the complex had been built of

smaller stone, and they were reduced to their foundations by Spanish builders in Cuzco.

Sacsayhuaman is a must-see.

We drove down the hill to Cuzco and a memorable Peruvian lunch at El Truco restaurant. The food was delicious--raw fish in lemon sauce, beef and pork, potato wedges in peanut sauce, chicken rolls, vegetables, soup, crusty rolls and guacamole, and for dessert, apple tart, rice pudding, and pineapple, and too much more even to sample--an interesting local ambiance, and the prices were very reasonable, about $11 for the sumptuous buffet. Some of the group had coffee, some water or soda, some coca tea with more leaves than water.

After lunch, Raul took us on a walking tour of old Cuzco. Ancient Qosqo was the principal city of the Incas, and there is still much evidence of their presence. When the Spanish arrived, they tried to erase all vestiges of Inca civilization, but they could not and decided instead to superimpose their structures and culture on the solid Inca foundations. Inca walls on Calle Loreto, for example, are topped by a second story of Spanish stone and masonry. Earthquakes routinely have brought down Spanish colonial structures while the Inca foundations remain standing.

The Plaza de Armas, fronted by Inca palaces, was considered the precise center of the Inca empire, and important religious and military ceremonies were held there. Today, visitors and residents alike wander about the landscaped square. The impressive cathedral on the plaza displays a happy blend of Spanish style and native Peruvian building skills. After seeing the interior, we walked across the plaza to visit an even prettier church, La Compañía.

Just off the plaza, we toured a structure the Incas called Koricancha, the Temple of the Sun, the Incas' principal place of worship. Interior walls were once covered with 700 sheets of gold, and a patio was filled with life-sized finely-worked figures in gold and silver of llamas, flowers, trees, fruits, and butterflies, sheep and lambs and shepherds. Gold stalks of corn, with leaves and ears, were planted in golden earth. A golden sun disk covered one whole wall, and a disk of silver on another wall represented the moon.

Koricancha is now within the Santo Domingo Church. Stout Inca walls and rooms still stand, bare of their treasure. The wall of one room contains the smallest extant stone laid by Incas. It is about one inch square, but still finely worked.

At dusk, we drove to the outskirts of the city to Incatambo Hacienda Hotel. The hotel has a nice colonial ambiance, beamed ceilings and an airy, pleasant dining room. Perhaps a bit too airy. The evening and night were cold, and the small space heaters in the rooms had little effect. As always, the staff were friendly and eager to please.

Early the next morning, we were off for Machu Picchu. Leaving all our luggage at the hotel except a small bag each, we rode our bus to the train station and boarded an interesting old steam train. The train puffed from the station, moved slowly forward and backward, again and again, up the switchbacks to the rim overlooking Cuzco. Once over the rim, the line descended to the Rio Urubamba at Ollantaytambo, then followed the river to Aguas Calientes. Here we got down, walked straight through lines of stalls and vendors without stopping--Raul assured the anxious shoppers in the group that we would come back--and to our bus. The bus began to negotiate the sharp switchbacks up the steep hillside.

Once at the top we quickly unloaded our gear at the Ruinas Hotel and regrouped on the

terrace. We  were only a stone's throw from the entrance to Machu

Picchu. For the rest of the morning, Raul led us through the ruin. He pointed out what was

known and commented on what was conjecture. We returned to the hotel for lunch, a crowded

affair since day-trippers eat here as well as hotel guests, then went back to the ruin.

The day-trippers from Cuzco and those staying at hotels in Aguas Calientes left by

mid-afternoon, and we had Machu Picchu to ourselves.

were only a stone's throw from the entrance to Machu

Picchu. For the rest of the morning, Raul led us through the ruin. He pointed out what was

known and commented on what was conjecture. We returned to the hotel for lunch, a crowded

affair since day-trippers eat here as well as hotel guests, then went back to the ruin.

The day-trippers from Cuzco and those staying at hotels in Aguas Calientes left by

mid-afternoon, and we had Machu Picchu to ourselves.

Later in the evening, we sat on the hotel terrace, sipping wine and coffee, and marveled at the beauty of the mountains, lofty, lush velvety-green peaks that towered above the river thousands of feet below. Clouds lowered and glistened about the crests of the mountains. The pink trout dinner in the almost empty dining room was delicious.

After an early breakfast, we returned to the ruin. Some of our group followed Raul up the Inca Trail to the Sun Gate, the pass in the mountain behind the ruin. Three hardy souls elected to climb Huayna Picchu, the peak that overlooks the ruin. The trail is almost vertical in places. The climb must be started at the bottom by 1:00 p.m. The view from the top is reported to be spectacular. Terraces at the very top of the peak can be seen from below.

My wife and I chose contemplation rather than exertion and exploration. We climbed to the small open structure that overlooks the ruin and faces Huayna Picchu. Agricultural terraces fan out on the side. We sat for over an hour and watched the changing moods of the ruin and the surrounding mountains. The early gloom began to lift, and the ruin to brighten. The heavy cloud that obscured Huayna Picchu thinned, layered and slowly dissolved. Rays of light pierced the overcast and illuminated the ruin. We looked below and saw only two people in the entire ruin, two from our group who had chosen to return to the site this morning.

We returned to the hotel to meet the group, "el grupo," they were now. The day-trippers had begun to arrive, and it was time for us to leave. We had already checked out and had only to board the bus. We sat on the terrace, waiting, sipping pineapple drinks in silence. The members of our group had had different experiences here, but all agreed that Machu Picchu was magical.

Just as the bus was pulling out, a boy of ten or twelve years,

dressed in Indian garb, waved to us from the side of the road. At the first switchback

down the hill, there he was, standing beside the road, waving. A couple of switchbacks

below, there he was again. He continued to appear from the roadside foliage all the way to

the bottom. He had run down a nearly vertical trail. We greeted him at the outskirts of

Aguas Calientes, took pictures, gave him some coins, and decided that he should train for

the Olympics.

Just as the bus was pulling out, a boy of ten or twelve years,

dressed in Indian garb, waved to us from the side of the road. At the first switchback

down the hill, there he was, standing beside the road, waving. A couple of switchbacks

below, there he was again. He continued to appear from the roadside foliage all the way to

the bottom. He had run down a nearly vertical trail. We greeted him at the outskirts of

Aguas Calientes, took pictures, gave him some coins, and decided that he should train for

the Olympics.

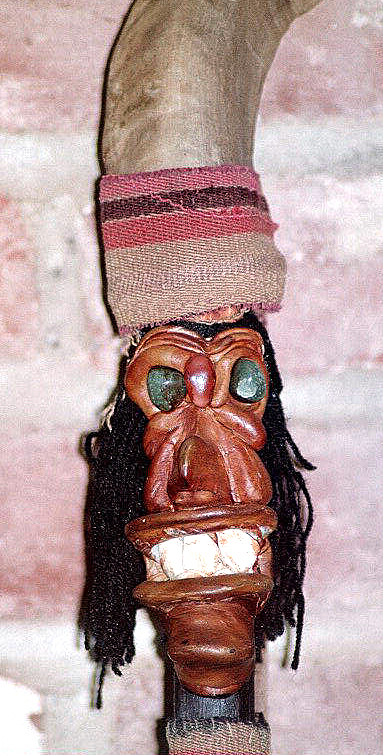

We had a fine lunch at the El Indio Feliz restaurant in Aguas Calientes. Chef Patrick

is French, and his wife, who manages the dining room, is Peruvian. There was time after

lunch for shopping. My wife bought a shirt, a doll, a necklace, and the ugliest walking

stick I have ever seen. Even the Peruvians, and later the Ecuadoreans, were impressed with

its repulsiveness. The top of the stick displayed in fired clay the features of a sneering

man, with yellowed teeth of corn kernels, coarse hair of straight black cloth braids, and

eyes of polished green stones. His hat was a goat horn. I was sure that the authorities at

some border point would refuse it entry, not because it contained animal and vegetable

parts, but because it was so repulsive.

of corn kernels, coarse hair of straight black cloth braids, and

eyes of polished green stones. His hat was a goat horn. I was sure that the authorities at

some border point would refuse it entry, not because it contained animal and vegetable

parts, but because it was so repulsive.

We boarded the train at 3:00 p.m. The ride up the scenic Urubamba Valley was pleasant, and the rain refreshing. As the rain slackened, and sunlight glowed against the dark clouds, a brilliant double rainbow appeared, with one end resting on a hillside on the left side of the train and the other dropping into the fields on the right side.

It was dark by the time we reached the Incatambo Hacienda. We had a late dinner at the hotel and then to bed.

An early flight took us to Lima, where we changed planes for Quito. Natalia, our guide for the Ecuadorean mainland, met us at the airport, and we were transported by bus to Hacienda Cusin, about one and a half hour's drive north of Quito.

This early seventeenth century Spanish hacienda, now converted to a country inn of

twenty-five guest rooms, suites and cottages, located at an elevation of 8,500' in the

Ecuadorean Sierra, is positively delightful. One can stroll in its forty acres of lush gardens on cobblestone paths and see the dozens of species of birds and

plants, or stop to browse in the library and take tea in the garden reading room. Flowers

are everywhere, in the gardens and in vases in all the buildings.

gardens on cobblestone paths and see the dozens of species of birds and

plants, or stop to browse in the library and take tea in the garden reading room. Flowers

are everywhere, in the gardens and in vases in all the buildings.

Nicholas Millhouse, the English owner, restored the hacienda in the early 1990s and continues his active administration of the property. A recent addition, The Monastery, adds fifteen guest rooms amidst gardens and fountain courtyards. Meals are served by candlelight in an elegant tapestried dining room, but informality is the rule. An inviting bar is located in the same building. The bar and most of the guest rooms have stone fireplaces where fires are kindled each evening, most welcome since the evenings were often cool in April.

Hacienda Cusin is self-contained and pleasant enough to stay within its walls for days, but the countryside beckons. We bused to Cuicocha Lake where we hiked to the rim for a scenic vista of lake and valley. On the road again, we stopped in the village of Cotacachi, famous for its leather products. The group was impressed with the high quality and low prices and bought purses, bags, and one member bought a handsome jacket at about one quarter of the price he would have paid in the United States.

On another day we drove to Agato, a small village that was noted for its woven goods. We watched weavers at the Tahuantinsuyo workshop and examined bags, sweaters, and rugs. I admired a particularly nice small wall hanging and pointed it out to one of our group. I liked it so much that I went to fetch my wife to show it to her. When we returned, it was gone. My friend was nowhere in sight. I admire the tapestry every time I go to her house.

One of our most interesting excursions was just outside the Cusin gate. In a walled compound across the road from the hacienda is Rosas del Monte, a renowned rose nursery. Forty to fifty thousand roses are cut each day for shipment all over the world, mostly to Europe. There are no regular tours here, but Cesar Maldonado, the Hacienda Cusin manager, arranged for our visit. We passed through a guard station and were told not to take pictures. Security is very tight, not only for economic reasons, but also to prevent the introduction of plant diseases. We went into a couple of the huge greenhouses and saw only perfect, beautiful roses. I remembered that I had marveled at the beauty of some cut roses in a shop at the leather village. We now learned that they were seconds. Cut flowers are an important industry in this region of Ecuador which has a rich top soil as deep as twenty feet.

There are many small craft villages in the area north of Quito, but none to match Otavalo. The market is supposed to be best on Saturday, but I cannot imagine that it could be more interesting than the Wednesday market that we visited. Even for one who does not shop, it is a must-see. Some vendors called out to advertise their wares, but most waited quietly for shoppers to show interest. They were friendly and not aggressive. Indicative of the variety of wares displayed at the market, my wife bought a woven backpack, a large cloth bag, three bracelets, a watercolor, necklace, mask, a small oil painting, and four small purses. If she had had a bearer, she undoubtedly would have bought more.

The last afternoon at Hacienda Cusin was free time. Some of our members returned to Cotacachi to look once more at the leather goods, others went horseback riding, and some stayed at the hacienda to read or wander about the gardens. My wife and I walked into San Pablo, the nearby village. The streets were lined with residences and shops that abutted the sidewalks, most with walled back yards. A little boy rode his plastic tricycle in the empty street, and a few adults strolled by. We photographed a picturesque stone church, closed and shuttered and showing the early signs of going to ruin, then walked to the nearby cemetery where children played among the concrete crypts. On our walk back to the hacienda, we waved to two boys on a donkey, one boy astride and the other standing behind him on the donkey's rump.

Early the next morning, we boarded the bus for the ride back to Quito. We had hardly left Hacienda Cusin when some members began talking of returning. It was that impressive. Enthusiastically recommended. I pondered divorcing my wife so we could remarry and book the honeymoon cottage set in its own gardens. Also, I had not seen the rare Andean condors that members of our party said they saw. I can't vouch for sightings of rare species that I don't see. I suspect they saw some huge Andean crows.

Natalia checked us in at the airport, and we were off for the Galapagos. Landing at Puerto Baquerizo Moreno on San Cristobal island, we were met by the guides from the M/V Corinthian, our home for the following five days.

First we had to get by the Galapagos park service officials at the airport. We had been warned that they would accept only clean, undamaged bills in payment of the $100 park fee. One of our members presented a $100 bill that was virtually new. It was rejected, so he tendered two $50 bills which they accepted. Another member offered a perfectly good $100 bill that was clean, probably not circulated, and only slightly creased. The park official examined it, tore it on the side, and gave it back to her. He would accept none of the other crisp, almost new bills she offered him. The man behind her in the line kindly offered her a $100 bill which the park official magnanimously accepted. Happily, I saw neither of these incidents, for I would have been furious. I can understand the park service's concern about counterfeit bills, but this is carrying concern to ridiculous lengths. If Ecuador wishes to encourage tourism, its very life blood, it must take greater care not to antagonize visitors with irrational obstacles.

We were bused from the airport to the quay where we were transported in launches to the Corinthian. I had booked my group on the little ship as a good compromise between the comfort of a cruise ship and the ambiance and camaraderie of the small island sailer. Carrying only forty-eight passengers in twenty-four staterooms, all with outside views, the air-conditioned vessel has a bar, lounges, jacuzzi on the top deck, small shop, library, and infirmary. The dining room can accommodate all passengers in one seating. The crew includes a team of naturalists and a full-time doctor. Zodiacs transport passengers to the islands, and kayaks are available for passenger use. The ship meets the U.S. Coast Guard standards for safety at sea.

After settling into our cabins and lunch, we motored around the island to Playa Ochoa where we snorkeled with moderate success. The beach was wonderful, and empty but for our party and a few sea lions who ignored us.

As we slept that night, the Corinthian moved to Genovesa, one of the more remote islands of the Galapagos. Landing by zodiac at Darwin Bay, we walked among nesting frigatebirds and red-footed boobies. We also saw doves, finches, gulls, and the omnipresent sea lions. Afterwards, we cooled off in the bay. The snorkeling was unimpressive.

After a refreshing lunch aboard and a rest in the shade on the top deck, we loaded into

the zodiacs for a landing at another site. We climbed a steep cliff face for a walk on the table land above. The trail lay through

patches of dry grass, then through thickets of stunted trees and bushes. We saw red-footed

boobies, frigatebirds, Darwin finches, doves, petrols, an owl, marine iguanas, and the

most curious mockingbirds. One settled on a branch just off the trail ahead and watched us

pass at eye level, within inches of it. Another alighted on the path ahead and looked up

at us as we walked around it. Then it ran along on the edge of the path until it was ahead

of us, turned around and watched us pass, completely unafraid.

face for a walk on the table land above. The trail lay through

patches of dry grass, then through thickets of stunted trees and bushes. We saw red-footed

boobies, frigatebirds, Darwin finches, doves, petrols, an owl, marine iguanas, and the

most curious mockingbirds. One settled on a branch just off the trail ahead and watched us

pass at eye level, within inches of it. Another alighted on the path ahead and looked up

at us as we walked around it. Then it ran along on the edge of the path until it was ahead

of us, turned around and watched us pass, completely unafraid.

Following our usual nighttime cruising, we visited the arid moonscape of Bartolomé, a small island off the coast of the larger James Island. We climbed the wooden stairway to the crest of an extinct volcano. Actually, it was a pretty small volcano, but before reaching the top, I would have sworn we had climbed a few thousand steps. Anyone who has seen pictures of the Galapagos would recognize the classic views from the top that include Pinnacle Rock, a tuff cone composed of solidified ash. Descending, we motored by zodiac around a point to a small bay where we saw a group of tiny endemic Galapagos penguins. One stood on a rock, as if posing, a rare treat, and about a half dozen others swam nearby. We were dropped off at a pretty white sand beach which we shared with sea lions. They played in the surf and lurched onto the beach beside us and sunned. The snorkeling was rather good.

We lunched on board as the Corinthian motored to the western side of James Island. There we walked on the beaches and by tide pools where we saw another penguin, oyster catchers, pelicans, mockingbirds, blue footed boobies, marine iguanas, and a giant sea turtle swimming lazily in a small cove. We saw not a few sea lions and some Galapagos fur seals. Here we had our sole encounter with the usual behavior of wild animals when a mother sea lion charged our group that had approached her pup too closely.

The next morning, we landed at Santa Cruz island. We hiked through a lush green landscape that finally erased my old perception of the Galapagos as barren and arid. We skirted a brackish lagoon where flamingoes walked majestically about, skimming the shallow waters for the pink shrimp that is their chief staple.

Continuing on our way, we parted the foliage that crowded the trail. I collided with

the guide when he stopped abruptly. He stepped aside to show me the huge land iguana that

lay in the middle of the trail. About three feet long, the iguana was a

brownish color with patches of yellow, orange, and red. I was mesmerized, a creature from

another time. He raised his head and faced away from us, as if to give us no more of his

time. He didn't move as we walked gingerly around him. An hour later when we returned, he

was still there, munching contentedly on a cactus leaf, the land iguana's principal food.

About three feet long, the iguana was a

brownish color with patches of yellow, orange, and red. I was mesmerized, a creature from

another time. He raised his head and faced away from us, as if to give us no more of his

time. He didn't move as we walked gingerly around him. An hour later when we returned, he

was still there, munching contentedly on a cactus leaf, the land iguana's principal food.

Sadly, the land iguana, though once so numerous that Darwin could not find sufficient space free of their burrows to pitch his small tent, is now an endangered species. They are no longer captured and roasted by man, but iguana nests and immature iguanas are at the mercy of introduced animals. Goats, dogs, and rats are particularly destructive. Adult iguanas are regularly captured and taken to the Charles Darwin Research Station on Santa Cruz Island for breeding. Offspring are eventually returned to their native islands.

Back on the Corinthian, we lunched and relaxed in the shade on the upper deck while we motored to Puerto Ayora on Santa Cruz Island. There we visited Darwin Station. Founded in 1961, the center is devoted to the preservation of the unique wildlife of the Galapagos. While the Station is concerned with all species on the islands, it is best known for its giant tortoises. Tortoise eggs are collected on the various islands, brought here and hatched. The tortoises are carefully identified so they can be returned to the specific island from which they came as eggs. Having now seen baby and adult giant tortoises, I can confirm that the giant tortoise was indeed the model for E.T.'s head and face.

Many visitors to the islands are surprised to find towns and farms, shops and ATMs. When the Galapagos National Park was created in 1968, it excluded approximately 3% of the islands' land mass, that is, land that was already occupied. The four towns, some agricultural land, and today's population of about 25,000, occupy this excluded land. The influx is nothing new. Our guide, William, was born in the Galapagos.

Leaving Darwin Station, we wandered the streets of Puerto Ayora, the islands' largest town and tourism center. Its chief product appeared to be T-shirts. Some of our group found liquid refreshment and relaxed in the shade. We soon returned to the Corinthian and a sumptuous farewell dinner, followed by local entertainment, musicians and dancers, on the top deck. The dancers invited us--then pulled us--onto the dance floor. I remembered the text of somebody's homily on how to live: "Work as if you don't need the money; Love as if you've never been hurt; Dance as if nobody's watching." And we did. The wine helped.

The next morning, we were bused to the San Cristobal Interpretive Center where we saw excellent exhibits that recount the natural and human history of the islands. The facility, whose construction was financed by the government of Spain, was opened only two years ago, and the Galapagueños are justifiably proud of it.

We returned to the ship for a last lunch and packed as the ship motored to Puerto Baquerizo Moreno on San Cristobal where we boarded our airport bus. Just before our departure, a lone marine iguana waddled up on the concrete slab beside the road and watched us pull away.

At the airport, I had one more anxious moment. My wife disappeared just as we were called to go to the boarding lounge. I could find her nowhere. Finally, at the last moment, she appeared, smiling broadly. She had been standing in line to have our passports imprinted with the Galapagos immigration stamp. The office had been empty, then the official appeared, but had considerable trouble opening the stuck drawer that contained the stamp.

Natalia met us at the Quito airport and transported us to the Quito Hotel. It was a nice enough hotel, but it had no local ambiance or charm whatever. Almost immediately on arrival, Natalia confirmed the high opinion that I had already formed of her. On unpacking, my wife was shocked to realize that her camera bag was missing. She had been so concerned about safeguarding her infernal walking stick that she had left the bag on the plane. She raced down to the lobby and found Natalia. Natalia called the airport and, to our great surprise, the plane was still at the gate, and the camera bag was found. Natalia went back to the airport and retrieved the bag. All was well, and we were able to enjoy a delicious, very inexpensive, dinner at nearby Kristy's Restaurant.

Next morning, we had a tour of Quito old town by bus and on foot. The traffic was formidable, all vehicles seemed to be honking simultaneously, and the air was badly congested. There were noticeably more beggars than we had seen elsewhere in Ecuador or Peru. We strolled in the palm-shaded Plaza de la Independencia and visited the cathedral whose interior was filled with paintings and artwork. Across the plaza, we saw the governor's palace where officials, surrounded by reporters and camera crews, conferred in the courtyard. Nearby, we marveled at the gold-encrusted interior of La Compañia, reputed to be Latin America's most beautiful church.

Boarding our bus, we motored to the northern outskirts of Quito to La Mitad del Mundo, the monument that sits on the equator. If you want to escape your shadow, this is the place to be on the equinoxes of March 21 and September 21. When the sun is directly overhead, you will cast no shadow. Or stand straddling the line and be in both hemispheres. Or stand on the line and claim to be not of this world. A tourist village surrounds the monument, offering souvenirs, refreshment, jewelry, woolen goods and local crafts of all sorts. The shoppers in our group, beginning to sense the end of the trip, scampered from shop to shop. If you're short on time, skip La Mitad del Mundo.

Returning by bus to our hotel, the group scattered for a last free afternoon. My wife and I had lunch with Natalia and two others at a small cafe. The sandwiches and berry drinks were superb. While Dennis and Maria, our group's consummate shoppers, headed for the outdoor market to look for leather goods, my wife and I visited the Museo del Banco Central. We were a bit taken aback at first by the soldier standing in the doorway to the exhibit hall, automatic weapon slung over his shoulder. But he smiled pleasantly, took our tickets and stepped aside. This excellent museum contains an account of Ecuadorean history through well-presented displays of art and dioramas in five salons devoted to archaeology, gold, colonial art, republican art, and modern art. A very rewarding visit.

It was time to begin moving toward our hotel, and my wife persuaded me to walk en route down an avenue of shops. From a box labeled "antiquities," she bought a small rough clay figure that was almost surely as old as six months, and a pan flute from a street vendor. After a few more blocks of window shopping, we sat for tea and watched passersby. I had my shoes shined by a polite little boy and don't think I endangered the local wage structure by giving him twice what he asked.

Next morning, we packed and departed, with fond memories of Peruvians and Ecuadoreans, Incas and Darwin. As we walked to the plane, my wife carried under her arm her walking stick, mercifully hidden under wrappings of newspaper, plastic bags, and cloth belts.

I enthusiastically recommend our two guides, in Ecuador, Natalia Rivera, lrivera@interactive.net.ec (that's lrivera, "l" as in "load"), and in Peru, Raul Gamarra Espinoza, punchao@hotmail.com. I particularly liked Posada del Libertador, our hotel in Yucay in Peru's Urubamba Valley, telephone 201115, fax 201116, and in Cuzco, and the Incatambo Hacienda Hotel, telephone (01) 4462062, fax (01) 2427811, 4471799. For the best experience at Machu Picchu, stay at the Machu Picchu Ruinas Hotel, telephone (51-84) 24-1777, fax (51-84) 23-7111. For information on Hacienda Cusin, which I heartily recommend, see their web site , hacienda@cusin.com.ec, fax (593) 691-8003, telephone (US) 800-683-8148, (UK) 181-788-7542. Tour arrangements were ably handled by Andean Treks, with offices in Massachusetts and Cuzco. The cost of the tour in April 1999 was $3,593 from Miami, a bargain. Write to Peter Robertson, president of Andean Treks, or telephone 800-683-8148.

This article published in International Travel News, November 1999.

|

Caveat and disclaimer: This is a freelance travel article that I published some time ago. Some data, especially prices, links and contact information, may not be current. |

|

|

|

|