RUSSIA: A NEW LOOK |

|

Harlan Hague |

Our arrival in Russia was not promising. We had just come from Finland where I was impressed with an atmosphere of friendliness and efficiency. Then we landed in Moscow.

We entered the small immigration hall to find a few hundred people packed tightly in front of two booths. There were no queues and no order. We joined the mass. The two agents worked slowly, methodically, often calling supervisors for consultation. Hundreds more entered the hall behind us, and pressed us even more tightly. No additional booths were opened though supervisors came and went. It was a magnificent power play or display of gross inefficiency. It required over three hours for us to move the thirty feet to the booth.Once through immigration, we collected our bags and followed the people that were sailing through the nothing-to-declare customs line. But not us. "No!" the agent said gruffly, waved us out of line and pointed. I had no idea where he wanted us to go, but we moved in that direction. We joined a queue of four or five people. When it was my turn, I smiled at the agent, said hello, and gave him the customs form furnished by Finnair.

"No!" he said gruffly--apparently part of the training of Russian customs agents--and pushed the form back to me. I looked at it to see what was wrong.

"New form!" he said and slid a blank form to me. I picked it up and walked over to a counter to fill it out. It was in Russian. I took it back to the agent."I don't read Russian," I said. I realized that his English was only one level above my Russian, which was zero, but I figured that he would understand.

"English form!" he said, pointing across the room. I collected the form. It asked for the same data as the old English form. We filled them out and finally made it through. All but half a dozen of our plane's passengers had breezed through customs, clutching the old forms. The representative from our cruise ship who met us outside customs said that the problem that we had had with immigration and customs had never happened before. Yeah, right.

I have always been fascinated with Russian history, but Russia was not tops on my travel list. It was however at the top of wife's, so that was settled. I had read glowing reports about the Volga cruise between Moscow and St. Petersburg on the M/S Russ, so I booked a triple cabin--our daughter had decided to go with us--for a departure in August 1999.

We finally boarded the Russ in late afternoon. It was docked at Moscow's Northern River Terminal. Symbolic of the Russian infrastructure today, though dating from only 1937, the building was crumbling, ill-maintained, yet still used and serving its purpose. It was still topped with a huge red star.

That was Saturday. Sunday was another day and the beginning of a most satisfying

exploration of Moscow. We began with visits to two metro stations--which have the look of

museums--and rides between them. Recommended. This was followed by a city bus tour which included Red Square. It was a

bit unnerving to stand where Stalin had stood when he reviewed the passing mass of soviet

military power. By the way, the "Red" of Red Square has nothing to do with the

color of communism."Red" in Russian means beautiful. The term is most

appropriate when applied to St. Basil's Cathedral at the foot of the square. Its onion

domes are familiar to anyone who has seen pictures of the square. We wandered a few

minutes inside GUM, the massive department store that borders Red Square before returning

to our bus.

That was Saturday. Sunday was another day and the beginning of a most satisfying

exploration of Moscow. We began with visits to two metro stations--which have the look of

museums--and rides between them. Recommended. This was followed by a city bus tour which included Red Square. It was a

bit unnerving to stand where Stalin had stood when he reviewed the passing mass of soviet

military power. By the way, the "Red" of Red Square has nothing to do with the

color of communism."Red" in Russian means beautiful. The term is most

appropriate when applied to St. Basil's Cathedral at the foot of the square. Its onion

domes are familiar to anyone who has seen pictures of the square. We wandered a few

minutes inside GUM, the massive department store that borders Red Square before returning

to our bus.

Beware of the portable chemical toilets at the bus park. When we were there in August 1999, they appeared not to have been emptied since 1997.

On another day, we entered the inner sanctum. After years of

wondering what went on inside the high walls of the Kremlin, our visit was most

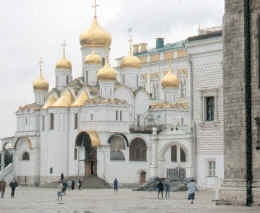

instructive. The Kremlin ("fortress" or "citadel") contains within its

sixty-eight acres government buildings, palaces, cathedrals of white stone, and the

Armoury, a magnificent museum. Dating from at least the fourteenth century, the Kremlin

has stood as a symbol of Russian power and piety, although the latter was denied during

the communist era.

On another day, we entered the inner sanctum. After years of

wondering what went on inside the high walls of the Kremlin, our visit was most

instructive. The Kremlin ("fortress" or "citadel") contains within its

sixty-eight acres government buildings, palaces, cathedrals of white stone, and the

Armoury, a magnificent museum. Dating from at least the fourteenth century, the Kremlin

has stood as a symbol of Russian power and piety, although the latter was denied during

the communist era.

The cathedrals are open again and are visited by throngs of Russians as well as foreign tourists. Cathedral Square, the oldest and principal square in the Kremlin, is bordered by three cathedrals: the Dormition, the Archangel Michael, and the Annunciation, masterpieces of Russian architecture. Czars and patriarchs were crowned in the Dormition, Russia's premier cathedral, even after the monarchy moved to St. Petersburg. The interiors of the cathedrals are as impressive as the exteriors. The focus of each cathedral is its iconostasis, literally a wall of icons, and walls and columns are decorated with paintings.

The iconostasis of the Cathedral of the Annunciation is particularly striking. Dating from the fifteenth century, it is one of the oldest in Russia and is filled with examples of some of Russia's most famous icon painters. Ivan the Terrible added considerably to the structure, including a separate entrance for himself. It seems that the patriarch had forbade him to use the main entrance since his many marriages offended the church. Many of the early czars are buried in the Archangel Michael Cathedral. Ivan the Terrible's tomb is behind the iconostasis.

The Armoury, one of the oldest museums in Russia, houses artifacts of all sorts dating

from throughout Russia's ![]() past. Holdings include collections of gold and silver objects,

including works by Peter Carl Fabergé--some of his fantastic Easter eggs are on

view--12th to 19th century weaponry, 13th to 19th century western European silverware,

most given as gifts to the czars, and an outstanding group of secular and religious

garments, some of Byzantine style dating to the early fourteenth century. A collection of

royal regalia and court ceremonial articles is unmatched in European museums. A group of

royal thrones is fascinating. The oldest is Ivan the Terrible's ivory-faced wooden throne.

A row of carriages displays Russian and western European works of art.

past. Holdings include collections of gold and silver objects,

including works by Peter Carl Fabergé--some of his fantastic Easter eggs are on

view--12th to 19th century weaponry, 13th to 19th century western European silverware,

most given as gifts to the czars, and an outstanding group of secular and religious

garments, some of Byzantine style dating to the early fourteenth century. A collection of

royal regalia and court ceremonial articles is unmatched in European museums. A group of

royal thrones is fascinating. The oldest is Ivan the Terrible's ivory-faced wooden throne.

A row of carriages displays Russian and western European works of art.

Tours typically do not devote enough time to the treasures of the Kremlin. Budget at least a day inside the walls.

We visited two additional museums, the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts and the State Tretyakov Gallery. The Pushkin houses original artifacts from the ancient Mediterranean countries, plaster replicas of sculptures from the Medieval period and the Renaissance, and western European paintings and sculpture from the Medieval period to the present. For anyone who has visited museums in western Europe, the museum will feel familiar.

![]() The Tretyakov is different. Displaying priceless collections of Russian

works of art, principally old icons and contemporary paintings, the Tretyakov is loved by

all Russians. I was fascinated by the delicate, finely detailed icons, even more beautiful

than those we had already seen in so many churches. I was profoundly impressed by the

works of Russian painters, names I had never heard. I cannot fathom why Russian art is not

better known in the west. Some of the landscape paintings on display compare equally with

any in galleries in Britain and the United States. If you are short on time, skip the

Pushkin, but don't miss the Tretyakov.

The Tretyakov is different. Displaying priceless collections of Russian

works of art, principally old icons and contemporary paintings, the Tretyakov is loved by

all Russians. I was fascinated by the delicate, finely detailed icons, even more beautiful

than those we had already seen in so many churches. I was profoundly impressed by the

works of Russian painters, names I had never heard. I cannot fathom why Russian art is not

better known in the west. Some of the landscape paintings on display compare equally with

any in galleries in Britain and the United States. If you are short on time, skip the

Pushkin, but don't miss the Tretyakov.

We signed on to three optional tours. The Sadko folk performance was entertaining, but I must admit that I enjoyed the dances and music of the costumed performers more than the vocal soloists and the dramatic conductor in black tails. Not a must-see if you must limit your options. There are other performances en route to St. Petersburg.

The second option, Kolomenskoye, was a pleasure after the hectic pace of Moscow. About an hour's bus drive from the capital, this was the site of a magnificent seventeenth-century fairy-tale wooden summer palace of the czars, long since vanished. The striking white Church of the Ascension, built in 1532 to mark the birth of the child that would be known to history as Ivan the Terrible, still stands, as well as some twenty other structures, notably the Palace Front Gates structure which houses a small museum.

The grounds also contain some historic

log buildings that were moved here from other parts of the country. These include Peter

the Great's house from Archangel, the entrance tower of the seventeenth-century St.

Nicholas Monastery in Karelia, and a tower of the Bratsky Stockade, a prison fortress in

Siberia, the seventeenth-century version of the mid-twentieth century gulags. On the

The grounds also contain some historic

log buildings that were moved here from other parts of the country. These include Peter

the Great's house from Archangel, the entrance tower of the seventeenth-century St.

Nicholas Monastery in Karelia, and a tower of the Bratsky Stockade, a prison fortress in

Siberia, the seventeenth-century version of the mid-twentieth century gulags. On the tree-covered footpath back to the bus, I stopped at

a bench where an artist had her paintings displayed. I bought an exquisite little

watercolor of the blue-domed Kolomenskoye church in the snow. A hundred steps more and I

took a photo where she stood to paint it.

tree-covered footpath back to the bus, I stopped at

a bench where an artist had her paintings displayed. I bought an exquisite little

watercolor of the blue-domed Kolomenskoye church in the snow. A hundred steps more and I

took a photo where she stood to paint it.

Our third option was the Trinity Monastery of St. Sergius at Sergiev Posad, about forty-four miles north of Moscow, and it was a delight. If you have time for only one trip outside Moscow, this is it. Founded in 1340 by Sergius of Radonezh, now St. Sergius, the patron saint of Russia, the walled monastery is still a place of pilgrimage for members of the Russian Orthodox Church.

The monastery throughout its history was influential in military and cultural affairs as well as religious. Sergius urged opposition to the Tatars in 1380, and the monastery was a fortress during the early seventeenth-century "Time of Troubles" when a Polish-Lithuanian force besieged the monastery for sixteen months. Monastery leaders subsequently inspired the uprising that expelled the invaders. The monastery was closed by the Bolsheviks, but Stalin permitted it to reopen as a museum and working monastery in 1946 as a reward for its support in the war. The monastery served briefly as the seat of the Patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church until it was moved to the Danilovsky Monastery in Moscow.

Trinity Cathedral, an integral part of the monastery, is at the very heart of Russian

Orthodoxy. A memorial service is conducted here every day around the clock to St.  Sergius, who is buried in the cathedral. Nowhere else

can one get such a moving impression of the devotion of the Russian people to their faith.

Worshippers are particularly drawn to an icon of the Old Testament Trinity in the

iconostasis, considered by some as the most important icon in Russia. It is a copy. The

original was taken from Trinity Cathedral and placed in the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow,

reportedly for safekeeping.

Sergius, who is buried in the cathedral. Nowhere else

can one get such a moving impression of the devotion of the Russian people to their faith.

Worshippers are particularly drawn to an icon of the Old Testament Trinity in the

iconostasis, considered by some as the most important icon in Russia. It is a copy. The

original was taken from Trinity Cathedral and placed in the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow,

reportedly for safekeeping.

The Cathedral of the Assumption, with its five starry blue and golden domes, is striking. A five-tier baroque bell tower is considered by some to be the most beautiful in Russia.

One can begin to understand something of Russia's history and culture by visiting Moscow and St. Petersburg, but to glimpse the soul of Russia, one must go to the Trinity Monastery of St. Sergius.

We left Moscow with much to see, but it would have to be left for another trip.  Our ship sailed on the Moscow Canal and the Volga River under a heavy

overcast and a light fog. It would be the same, with intervals of rain and sunshine, for

the remainder of the voyage. The banks were mostly wooded, with occasional hamlets of

dachas and scattered farms and villages. Men fished from the banks and in boats that

seemed too small for safety. We passed many locks, down at first to reach the lower level

of the Volga, then up as we ascended the Volga toward St. Petersburg.

Our ship sailed on the Moscow Canal and the Volga River under a heavy

overcast and a light fog. It would be the same, with intervals of rain and sunshine, for

the remainder of the voyage. The banks were mostly wooded, with occasional hamlets of

dachas and scattered farms and villages. Men fished from the banks and in boats that

seemed too small for safety. We passed many locks, down at first to reach the lower level

of the Volga, then up as we ascended the Volga toward St. Petersburg.

An all too common sight along the Volga was the abandoned and

derelict factories, testaments to Russia’s severe economic problems. Economic decline

contributed to the collapse of communism, but the decay accelerated in the tumultuous

birth of democracy and capitalism.

An all too common sight along the Volga was the abandoned and

derelict factories, testaments to Russia’s severe economic problems. Economic decline

contributed to the collapse of communism, but the decay accelerated in the tumultuous

birth of democracy and capitalism.

One of the most melancholy sights I have ever seen is the flooded belfry of the St. Nicholas Cathedral of Kalyazin. The tower pierces the surface of the river to mark the center of the town of Kalyazin. Stalin ordered the town leveled and the area flooded to provide water for the Uglich power plant, which itself was built on the site of a historic monastery which was blown up.

As the Russ approached the Uglich quay, the sounds of a plaintive Russian

folk song drew me to the rail. Before we  docked, the group on the pier switched to a

rousing "Hello Dolly". I went below.

docked, the group on the pier switched to a

rousing "Hello Dolly". I went below.

Uglich, founded in 1148, is best known as the site of the murder in 1591 of Prince Dmitry, youngest son of Ivan the Terrible, thus the name of the starry-domed Church of St. Dmitry on the Blood, built in 1692. At the nearby green-domed Transfiguration Cathedral, in the high vaulted chamber we heard a wonderful small men's choir, one of the best I have ever heard.

On the path back to the ship, we passed lines of small stalls exhibiting local crafts of all sorts. I was surprised to hear an American voice offering goods at a table. She was from Washington, a volunteer at a local orphanage. I purchased a set of napkins made by the children. A bit further on, I bought a sprig of flowers from an old woman who was too proud to beg. I was touched by her gratitude for the dollar that I gave her, the denomination suggested by tour organizers. Near the quay, I stopped where three old women stood together, holding small bunches of flowers. I gave a dollar to one woman, and she tried to give me all her flowers. A second woman pressed in, and I gave her a dollar, and she gave me a sprig. The third offered her flowers, and the other two pled with their eyes for me to give her something, but I had exhausted my dollar bills, and walked on. She followed me, with tears in her eyes until I reached the quay.

Her face haunted me. I went below, retrieved more dollars and went back ashore. The

three women saw me coming, and the two turned to the

third who smiled sweetly at me, and the tears came again. I have never been so profoundly

moved as I was by her expression of thanks. Before leaving the ship in St. Petersburg, I

made arrangements for someone on the return voyage to find the three women and give them a

gift of money in exchange for their flowers.

the

third who smiled sweetly at me, and the tears came again. I have never been so profoundly

moved as I was by her expression of thanks. Before leaving the ship in St. Petersburg, I

made arrangements for someone on the return voyage to find the three women and give them a

gift of money in exchange for their flowers.

Leaving Uglich, we sailed into the Rybinsk Reservoir, then down a branch of the Volga to Kostroma. Dating from the early thirteenth century, the city itself is unremarkable, reportedly a typical example of a Russian provincial town. It is best known for its Ipatievsky Monastery and as the birthplace of Michael Romanov, destined to become the first Romanov czar in 1613. We visited the Trinity Cathedral, where a wonderful choir of six young women sang for us, then walked across the way to a museum of the Romanovs where Michael had lived for a time. The museum houses mementoes of the Romanovs and photographs of the later Romanovs. The glass on many of the pictures is shattered, symbolic of the murder of the family in 1917. Inside the nearby Epiphany Convent, we saw an icon of the Romanov family, a golden Madonna and child whose faces appear to be black until one moves close.

We strolled down a residential street lined with weathered old decorated wooden houses.

Failing to find stalls to satisfy the shopping instincts of Carol and Merrilee, my wife

and daughter, we walked back to the ship. We paused in a park to ponder a huge statue of

Lenin, one of the few we had seen, and

arrived at the quay to find vendors behind tables covered with local crafts. I said

goodbye to Carol and Merrilee, but they were busy and ignored me.

of the few we had seen, and

arrived at the quay to find vendors behind tables covered with local crafts. I said

goodbye to Carol and Merrilee, but they were busy and ignored me.

Yaroslavl was the next stop. After a bus tour of the historic city, founded in 1010 and briefly the Russian capital during the Time of Troubles, 1598-1613, we visited a puppet museum and crafts sale. The lacquered boxes were beautiful, some selling for as much as $2,000. I passed, but one member of our group bought an exquisite little box for almost $600.

We stopped next at the seventeenth-century church of St. Elijah the Prophet where we admired frescoes that completely cover walls and high ceilings and the icons that date mostly from the 1670s. Unique carved wooden thrones for the czar and patriarch face the iconostasis. In the smaller winter hall of the church, we were entertained by a wonderful men's quintet.

On to the Savior- Transfiguration Monastery which has served both God and man. The walled monastery was a fortress during the Time of Troubles. Here we heard a demonstration of stringed bell-ringing and climbed the monastery tower. The view is worth the steep climb. It was interesting to be at eye level with the onion domes. We then bused to the town hall for a folk concert. I liked the performance even better than the Sadko in Moscow. If you must make choices, opt for the included show in Yaroslavl.

Underway again, we sailed back upstream to enter the Rybinsk Reservoir, passing the huge statue of Mother Volga, seemingly a romantic tribute to the mighty Volga, but actually a declaration of Socialist success in electrifying the country. We passed through the reservoir at night, so large that it is often called a sea, and reentered the Volga.

We docked the next morning at Irma for a recreation or

"green" stop. The docking place is at a meadow where we were scheduled for a

Shashlyk (shish-kebab) picnic ashore, but a threat of rain kept us on the ship for lunch.

At the first opportunity, Carol and Merrilee went ashore while I remained on board to fish

over the side. Anyone who caught a fish was to be rewarded with a bottle of champagne.

We docked the next morning at Irma for a recreation or

"green" stop. The docking place is at a meadow where we were scheduled for a

Shashlyk (shish-kebab) picnic ashore, but a threat of rain kept us on the ship for lunch.

At the first opportunity, Carol and Merrilee went ashore while I remained on board to fish

over the side. Anyone who caught a fish was to be rewarded with a bottle of champagne.

After investigating the shopping opportunities at tables set up on the quay, Carol and Merrilee walked up the hill to the village which sits on a rising about a hundred yards from the dock. They looked over the four or five goods tables set up in the village crossroads, then accepted the invitation of one of the vendors to visit her house. We had been told by Russ personnel that Irma residents do this both to extend hospitality and to earn some extra money.

Carol and Merrilee enjoyed the visit immensely and brought me up the hill later to

introduce me to their new friends. They were still at their table. We speak no Russian and Zoya did not speak English, but

Zhenya, her daughter, a university student, spoke enough English to make the meeting

understandable. Carol gave them a sack of fruit that we had accumulated from our meals. We

had been told that fresh fruit was so expensive in Russia that most people saw little of

it. While we delayed over the last table of goods, Zoya ran back to her house and brought

each of us a cookie and small piece of wrapped candy.

table. We speak no Russian and Zoya did not speak English, but

Zhenya, her daughter, a university student, spoke enough English to make the meeting

understandable. Carol gave them a sack of fruit that we had accumulated from our meals. We

had been told that fresh fruit was so expensive in Russia that most people saw little of

it. While we delayed over the last table of goods, Zoya ran back to her house and brought

each of us a cookie and small piece of wrapped candy.

While Carol and Merrilee were on their first visit in Irma, I was being humbugged in the fishing contest. About eighteen or twenty of us lined the rail. I lost my bait a dozen times to small nibblers. One compatriot down the line caught a six-incher. I lost more bait. After an hour of this, Zena, a ship’s officer, came by and said that the desk wanted to ask me a question. She said she would hold my pole. At the desk, Olga asked me something about my laundry. All was in order. I should have suspected something.

I went back out and Zena handed my pole to me. She looked down at the water and exclaimed theatrically that I had a bite. I knew I had been had. I pulled in the line to retrieve a stiff pickled herring. I had wondered about the crewman who had been standing at the rail when I first arrived that morning. He had remained at his post with his line in the water, no cork, and obviously bored. Zena had exchanged his pole for mine while I was below. No matter, I received two bottles of champagne. Later, Carol and Merrilee walked around the deck with me, and we poured for anyone who would accept our offering.

We steamed all the next day, through White Lake and the Kovzha River, part of the Volga system, to Lake Onega. Banks were mostly wooded, with openings where we saw rural hamlets, cultivated fields and haystacks, and clusters of dachas.

The next day we arrived at Kizhi island in the rain and a heavy overcast. The principal

attraction here is the magnificent wooden twenty-two-domed Transfiguration Cathedral.

Dating from 1714, it was constructed as a summer church, entirely without nails, to commemorate

Russia's victory over the Swedes in the Time of Troubles. The cathedral is not open, but

we did see the inside of the smaller wooden Intercession Church adjacent, the winter

church, which houses icons from the cathedral. The churches survive because the Bolsheviks

decided that they were the product of proletarian genius and should be preserved.

constructed as a summer church, entirely without nails, to commemorate

Russia's victory over the Swedes in the Time of Troubles. The cathedral is not open, but

we did see the inside of the smaller wooden Intercession Church adjacent, the winter

church, which houses icons from the cathedral. The churches survive because the Bolsheviks

decided that they were the product of proletarian genius and should be preserved.

An outdoor museum was added in 1966, and wooden structures, such as bell towers,

peasant houses, barns, chapels, windmills and granaries, were moved here from the Onega region. A most

satisfying visit, in spite of the unpleasant weather. In such circumstances, I remind

myself that if I wish to experience a place rather than simply see it, I must

accept whatever conditions I find, as residents must do. My only regret is that we missed

the island's picturesque little cemetery. I learned of it after our departure.

and granaries, were moved here from the Onega region. A most

satisfying visit, in spite of the unpleasant weather. In such circumstances, I remind

myself that if I wish to experience a place rather than simply see it, I must

accept whatever conditions I find, as residents must do. My only regret is that we missed

the island's picturesque little cemetery. I learned of it after our departure.

We steamed across the lake to Petrozavodsk "Peter's Factory Town") on the

western shore. Founded in 1703 by Peter the Great as an armaments factory, the town grew

as czars and Bolsheviks later banished dissidents there. Our bus tour in the rain was

difficult, but interesting nevertheless. The tour ended at the city concert hall where we

were entertained with a performance of Karelian dance and Karelian-Finnish instruments by

the Kantele group. Quite different from anything we had seen before and very enjoyable.

Afterwards, there was the inevitable craft  shopping in the foyer. The omnipresent sale

tables were becoming a bit tedious, but others in our group--including wife and

daughter--looked forward to them, and I knew how much the local people relied on sales to

tourists.

shopping in the foyer. The omnipresent sale

tables were becoming a bit tedious, but others in our group--including wife and

daughter--looked forward to them, and I knew how much the local people relied on sales to

tourists.

During the night, we cruised on Lake Onega and entered

the Svir River. A few kilometers after passing the village of Podporozhye, we docked for a

"recreation stop" at Mondraga, a picturesque meadow bordered by dense forest.

Near the quay, tented venues offered food, local crafts, honey, and beer. A popular stop

was a log building which houses a museum of vodka and sells a wide variety of vodka.  A rustic hotel and restaurant and other buildings

were under construction. I doubt that the original village that once occupied the site

looked anything like the trim, upscale holiday structures that are going up.

A rustic hotel and restaurant and other buildings

were under construction. I doubt that the original village that once occupied the site

looked anything like the trim, upscale holiday structures that are going up.

Boarding in the early afternoon, we sailed up the Svir River and entered Lake Ladoga, Europe's largest lake. We steamed along the southern reaches of the lake, passing many small villages, and entered the Neva River, arriving in St. Petersburg by morning.

St. Petersburg was meant from its beginnings to be Russia's window to the West. At first glance, it indeed appears more western than Russian. But this is looking at the outside. Inside, in spirit and focus, Petersburg is Russian to the core. Our visits during the following three days revealed the city's role in czarist, Soviet, and modern Russia.

We were treated to a bus tour of St. Petersburg's center with a running commentary on the city's origins. Peter the Great in 1712 moved the Russian capital from Moscow to Petersburg in 1712, which had been built on his orders during the past decade. The seat of government would remain here until Lenin in 1918 moved it back to Moscow. The city name’s had been changed in 1914 from the German-sounding St. Petersburg to Petrograd. When Lenin died in 1924, the name was changed again, now to Leningrad. In the emancipating atmosphere of Mikhail Gorbachev's perestroika and glasnost, the city's inhabitants by vote changed the name back to St. Petersburg.

The Peter and Paul Fortress was a bit of a disappointment. Peter the Great had the

bastion built as a refuge against Swedish attacks, but it served as a prison for most of

its useful life. We viewed the massive structure from outside and from within the

impressive courtyard, but were only admitted to the toilets and a single upstairs room

that served more as a shop than any historic function. Little was purchased since prices were, I was told by the shoppers, about three times those

of other locations. I was more interested in the Peter and Paul Cathedral whose tall

needle-like spire seems to pierce the heavens. Most of the Romanov czars, including Peter

the Great, are entombed in the cathedral. Outside the walls on a pier, we heard a musical

group, including quite a good operatic baritone, performing for tips, a sad commentary on

Russia’s economic troubles.

prices were, I was told by the shoppers, about three times those

of other locations. I was more interested in the Peter and Paul Cathedral whose tall

needle-like spire seems to pierce the heavens. Most of the Romanov czars, including Peter

the Great, are entombed in the cathedral. Outside the walls on a pier, we heard a musical

group, including quite a good operatic baritone, performing for tips, a sad commentary on

Russia’s economic troubles.

After sack lunches on the bus, we went to St. Petersburg's piéce de resistance: the Hermitage. Actually a complex of five buildings dating from the mid-eighteenth to the mid-nineteenth centuries, this mother of all museums houses almost three million works of art in four hundred rooms, so many that, it has been said, to pause just a few moments at each would require nine years. Pieces have been added by purchase, war, donation, and confiscation. Stalin reversed the inflow when he sold pieces to earn foreign exchange. Before the Bolsheviks came to power, the magnificent collections were largely for the court's enjoyment. Catherine the Great once wrote in a letter: "All this is admired by mice and myself." The Hermitage was opened to the public by the Bolsheviks in 1917.

Instead of nine years, we spent an afternoon in the Hermitage. We were guided through as one brushes one's hand over a velvet cloth, touching the top and gaining an impression of the richness of the whole. We saw treasures of the western European masters--paintings, sculptures, prints, drawings, jewelry, medals and coins--so much elegance that one is almost overwhelmed. The buildings themselves are also works of art. At the end of our tour, we enjoyed a walk through the living quarters of the czars, an optional add-on.

The highlight of the next day was a drive outside the city to the town of Pushkin, a summer haven for the czars, and a visit to the Palace of Catherine the Great. The palace may be even more impressive than the Hermitage. Its blue exterior with white trim and gold decoration is striking. The palace is fronted by extensive formal gardens. Inside, the richness of the decoration is almost overwhelming. A woman in our group actually gasped as we entered one room. It was a gingerbread of gold and silver. Could anyone really live here in such opulence? Much of what we saw was reconstruction, since the palace was gutted by German shelling and bombing during World War II, but the work has been a faithful resurrection of the pre-war building. Most impressive.

Returning to St. Petersburg, we stopped at St. Isaac's Cathedral. This is a church in the western style, no onion domes here. The architect was French. Like St. Petersburg, the church may look western European on the outside, but inside it is pure Russian, though still different in appearance.

The interior is a blending of sculpture, mosaic, paintings and murals. The facing of the iconostasis is carved white marble, fronted with pillars of malachite and lazurite. Some of the icons are traditional paintings, others are mosaic. Consecrated in 1857, St. Isaacs quickly became the city's leading cathedral. The Soviets converted the church to a museum. During World War II, the building was closed and became a warehouse for area museums. Officially still a museum, St. Isaacs has been returned to the Orthodox Church, and services are held on certain religious holidays such as Christmas and Easter.

Carol, Merrilee and I left the group at this point and took a taxi to The Church of the Saviour on the Blood, also called the Church of the Resurrection of Christ. Zoya was waiting for us.

Dr. Zoya Zarubina, whom we met on the Russ where she was a lecturer, is a bit of a legend in Russia, and we were still in awe of her. She was a KGB officer during and after WWII. We talked for hours about the war and the relations between the Soviets and the United States. I am an historian and I said to Zoya that I would love to have been a fly on the wall at Yalta to know exactly what was said. She touched my arm and said sofly: "I will be your fly on the wall. I was there." Zoya was one of the Soviet Union’s top translators and worked with Stalin, Roosevelt and Churchill. She translated the American atomic bomb papers after her KGB father’s intelligence organization in the United States stole them.

Zoya also is a devout Christian and has been all her life. When she told about her faith one afternoon in the ship foyer, a listener was visibly unconvinced. Zoya smiled at her and asked her if she found this hard to believe. The woman replied that KBG and Christianity did seem to be a bit contradictory. "Do you mean," Zoya asked, "that your CIA agents could not claim to be good Christians?"

Zoya today is a leader in world peace movements and women’s movements. She is involved in many charities for children, the disabled and the elderly. At the end of the cruise, she was going to tutor a group of women who were running for election to the Duma, the Russian equivalent of Congress. She has been a lecturer at the Diplomatic Academy in Moscow for thirty years.

Zoya had already bought our

tickets for the Church of the Saviour on the Blood and led us inside. My jaw dropped.

Really. The interior is magnificent. Almost everything is mosaic: icons, pictures, walls,

columns and arches, ceilings, floors, even the cupola. Stonework is composed of rich and

many-hued marble, jasper, rhodonite and porphyry. The church is light and airy, the people

quiet and subdued.

Zoya had already bought our

tickets for the Church of the Saviour on the Blood and led us inside. My jaw dropped.

Really. The interior is magnificent. Almost everything is mosaic: icons, pictures, walls,

columns and arches, ceilings, floors, even the cupola. Stonework is composed of rich and

many-hued marble, jasper, rhodonite and porphyry. The church is light and airy, the people

quiet and subdued.

The church is built on the site of the murder in 1881 of the reformist Czar Alexander II by a terrorist. It was never meant to be a parish church, rather a memorial for the fallen czar. The only services were those in memory of Alexander, though a sermon and requiem were said regularly. In 1917, the Bolsheviks opened the doors to the public. When St. Isaacs was closed in the 1920s, the Saviour on the Blood functioned briefly as the cathedral church until the Soviets closed the doors in 1930.

The structure is a romantic impression of late eighteenth-century Russian church architecture, the exterior at least. The brick walls are busy, ornamented with carved marble arches, short columns, an elaborate cornice of brick and marble, mosaic representations of saints and a great variety of images. Cupolas are roofed with blue, lime, yellow, and white tiles. Most of the domes are gold-plated, one is covered with spiky cubes, and the topmost appears as a multi-colored turban. Some call the structure garish, a sort of Russian Neuschwanstein. Others love it. I love it, inside and out. Neuschwanstein too.

Leaving the church, Zoya took us to another favorite of hers, Kazan, once a museum of

atheism, now a church. Afterwards, we visited shops and rode the tram back to the ship.

Leaving the church, Zoya took us to another favorite of hers, Kazan, once a museum of

atheism, now a church. Afterwards, we visited shops and rode the tram back to the ship.

On Friday, we were bused to Petrodvorets (Peterhof). We walked in the gardens and among the many beautiful fountains, then walked through the palace. Returning to St. Petersburg, we embarked on the canal cruise. St. Petersburg is hardly the reputed "Venice of the North," but one gets an interesting view of the city from the canals. We finished the evening with the Cossack concert. Interesting, but not a must-see. I think I was a bit disappointed since I had seen a rousing, moving Cossack concert in Berkeley years ago, and this one didn’t equal that performance.

This was a memorable trip. The ship was first-rate, and the service was commendable. Our triple cabin was not as well situated as the double cabins, being below deck with only a porthole, but it was as we expected. The food was good and varied, and restaurant service was excellent, though I do chafe at assigned seating which is for the convenience of staff rather than passengers. Perhaps it is necessary if one is to have choices, but I wonder whether some compromise could be developed. We were entertained nightly by informal performances by Yuri Nugmanov, one of Russia’s leading classical guitarists, and he was magnificent.

One negative comment: We departed Moscow on Tuesday at 5:30 p.m. and sailed overnight. On Wednesday at 9:15 a.m., still underway, an "Obligatory Talk on Safety Measures" was delivered in the movie hall. I suppose accidents that might endanger the ship and its occupants are not permitted on Tuesday nights.

This trip was an eye-opener for me. Some of my perceptions of Russian history and society were confirmed, others were changed and new impressions formed. While I am aware of Russia’s serious economic troubles and social problems, I am now more optimistic about her future. Zoya Zarubina was in no small part responsible for my new view of Russia. Russians are realists, she said, they know that they are living in hard times, but they believe that a better life is ahead, and they are willing to work hard for it. A biography of this remarkable woman was published in 1999, Inside Russia: The Life and Times of Zoya Zarubina, by Inez Cope Jeffrey, Austin: Eakin Press.

We booked our Russian cruise from GT Cruises in Brooklyn, 800-828-7970. Alex was responsive, efficient and helpful. Billing was clear and prompt. The only downer is that we were not informed in advance that our flight on the St. Petersburg-Helsinki segment was changed from Finnair to Pulkovo Aviation Enterprise, a Russian contract airline whose service and equipment were not satisfactory. The cost of our tour, including the triple cabin, from San Francisco was $2,387.67 each, which included a mandatory overnight in Helsinki on the eastward journey.

|

Caveat and disclaimer: This is a freelance travel article that I published some time ago. Some data, especially prices, links and contact information, may not be current. |

|

|

|

|