TURKEY AND THE TURQUOISE COAST |

|

Harlan Hague |

My announcement that I was going to Turkey almost invariably elicited one of two responses.

"Why are you going to Turkey?" This from people who had never been to Turkey. From people who had visited Turkey: "Wonderful! You’ll love it."

Turkey has become one of the most popular destinations in the world, mostly with Europeans, but Americans are discovering it as well. Americans who go to Turkey are well-traveled, so they can make comparisons. It is therefore impressive that so many say that their Turkey trip was one of their favorites.

A first visit to Turkey, particularly if one is unsure of returning, should include at least four areas: Istanbul, Cappadocia, the Mediterranean coast west of Antalya, and Ephesus.

We began our visit in September 2000 in Istanbul. Our small band, which I had put together, joined others in Istanbul, bringing the total group to twelve. We had been fourteen, the maximum size determined by the capacity of the gulet, the motor-sailer which we would board later in the tour, but a couple had withdrawn at the last minute.

After a long, tiring flight from San Francisco via New York’s JFK airport, the

passage through Istanbul’s Atatürk Airport immigration was reasonably efficient, and

we walked through customs. We were met by Ahmet, Overseas Adventure Travel’s guide,

at the exit. Before leaving the airport, I stopped at an ATM to buy Turkish lira and

became an instant millionaire. At an exchange rate of 665,000 to 1, my US$75 bought fifty

million lira. I have juggled dozens of currencies in my travels without too much

difficulty, but I never quite got used to paying a million for a shoe shine or an ice

cream bar. I wondered later what my friends at home would think when I told them that the

bar bill for my wife and me at our hotels was never less than twenty million a day.

shine or an ice

cream bar. I wondered later what my friends at home would think when I told them that the

bar bill for my wife and me at our hotels was never less than twenty million a day.

Our hotel in Istanbul, the Blue House Hotel, was delightful, just the sort that I like. It is older, but modernized, small with a nice local atmosphere, outside tables for lunch and dinner, and a light, airy dining room where a buffet breakfast was served each day. The location was ideal, in the Sultanahmet district of the old town across the street from a small bazaar and with a view of the Blue Mosque. Our walking tours began at the door of the hotel.

On our first morning in Istanbul, I asked one of our tour members how she had slept. She said that she woke up early, "before the minaret went off." I had been jarred awake when the amplified call to prayer from the Blue Mosque sounded clearly and loudly at about 5:00 a.m. Then a muezzin from another mosque answered in like fashion, and they bounced the call back and forth for what seemed an eternity. On subsequent days, in Istanbul and elsewhere, I either did not hear the early call or was able to go back to sleep easily. The calls became unobtrusive, even comforting.

One who has heard of the devotion to prayer and ritual in other Moslem countries will be surprised to see few Turkish people praying in public, women dressed in the latest fashions, and advertising which displays as much near nudity as seen in the United States and Europe. Turkey is a secular country where religion is respected and practiced, but which has no political power.

Istanbul’s cultural riches center on its mosques and palaces. Aya Sofia (Hagia Sofia), dating from 537 A.D., has survived earthquakes, hooliganism, and looting and desecration by crusaders and others. Built by the Byzantine Emperor Justinian as a church, it was converted to a mosque by Mehmet the Conqueror after Constantinople’s fall to the Ottomans in 1453. The huge structure was in turn converted by Atatürk to a museum in 1932. Defacing by Catholic crusaders is visible, and Mehmet removed many images, but some important Byzantine mosaics remain in the gallery.

Nearby Sultanahmet Camii (Blue Mosque) was built by Sultan Ahmet in 1617. It is smaller than Aya Sofia, but it is more architecturally coherent and has a beautiful interior. It is best seen on a bright day when light from the windows in the cupola illuminates the tiled surfaces. The elevated belt of blue tiles gives the mosque its popular name. The structure’s striking six minarets add to its balance. The light show on the exterior on summer evenings, narrated in a different language on four successive nights, is entertaining but can be missed.

We also visited the Süleymaniye Camii, or the Süleyman the Magnificent Mosque, the largest in Istanbul and the second largest in Turkey. The mosque was built in the mid-sixteenth century during the richest period of the Ottoman empire. The simple interior adds to its appeal. We had dinner at the Darrulziyafe Restaurant, originally the imaret, the compound’s soup kitchen. No alcohol with the meal this evening, too close to the mosque.

In the modern city of Istanbul, as in all of Turkey, one sees many remnants of the Greek and Roman pasts. We walked across the pleasant park that was the Hippodrome, the Roman Circus. Dating from 203 A.D., the original structure had seating for 100,000 spectators. The emperor’s box once featured four magnificent bronze horses. I remembered seeing them in St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice. They were part of the plunder taken home by Venetian crusaders.

Antiquities from Turkey can be found in museums all over the western world, stolen during centuries of crusades and imperial expansion. It should also be noted that many of the statues, monuments and trophies that decorated the ancient Roman Hippodrome in Istanbul were foreign plunder. The oldest remaining structure, the obelisk of Theodosius, came from Egypt in the fourth century. The Serpentine Column was brought here from the Oracle at Delphi in Greece.

Nearby we descended below the surface into the cool Yerebatan Saray or "Sunken Palace". The huge cistern, whose roof is supported by 336 marble columns, was built by the Emperor Justinian as a water supply for Constantinople. With a background of classical music, we walked along the catwalks above the shallow water where small fish swam. At the back of the cavern are two curious upside down capitals with medusa heads. The builders used whatever materials they had at hand.

Leaving the cistern, we walked to The Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art on the eastern side of the Hippodrome. Originally the home of Ibrahim Pasha Sarayi, Suleiman the Magnificent’s Grand Vizier, the 16th century structure displays examples of Islamic art and calligraphy, historic carpets and silver, and representations of home interiors and dress. A café in a pleasant courtyard serves Turkish tea and pastries. After finishing the thick tea, turn the cup upside down, and ask someone to tell your fortune from the dregs on the saucer.

Our walking tour ended at Topkapi Palace. Built by Mehmet the Conqueror in the mid-15th century, this magnificent palace was home to the Ottoman sultans until the mid-19th century. It is a museum today, housing collections of sculpture, jewels, manuscripts and other memorabilia of the Ottoman empire. It would require the better part of a day to see the huge complex well. A couple of hours is sufficient for a glimpse of most of the important structures and collections. There is a restaurant at the end with a nice view of the Bosphorus and the Golden Horn.

Leaving Topkapi, our group boarded a boat at the Sirkeci station for a cruise in the Bosphorus. It was a sunny windy day, cool and refreshing. We had a sixty-passenger boat to ourselves. Refreshments were available, and the hot tea was most welcome. We sailed northward against a strong current—the Black Sea is higher than the Aegean—passing along the European side, with its government buildings and mosques and business and residential neighborhoods. Then we turned to cruise southward on the Asian shore, featuring a less pretentious business and official development, with the exception of the posh "Bosphorus houses" that line a sizable stretch of the waterfront. Ahmet pointed out the house that he intended to buy. Yeah, right. We had dinner in a restaurant on the Asian side, popular with locals.

Returning to the hotel, Carol—my wife--and I walked across the street to the busy bazaar. Small cafes and shops were crowded with locals and tourists. We watched two dervishes dancing. The spinning figures, accompanied by music, were almost hypnotizing.

We were up early the next day for a flight to Kayseri in Cappadocia ("Kapadokya" in Turkish), southeast of Ankara. Our minibus, with plenty of room for our small group to stretch out, fetched us at the airport and drove a couple of hours to Ürgüp where we stopped for lunch.

After lunch we climbed "the fortress," a

tall rock formation. From the top, we had our first look at a landscape unlike any other

on the globe. Cappadocia is a semi-arid region that is covered with a deep layer of soft

rock called "tufa," composed of volcanic lava and ash deposited millions of

years ago by four now extinct volcanoes. Wind and water have created a heavily eroded

moonlike terrain where bits of hard basalt have protected the underlying tufa from

erosion, leaving towers that often still wear their basaltic caps. These are the

"fairy chimneys" of Cappadocia.

After lunch we climbed "the fortress," a

tall rock formation. From the top, we had our first look at a landscape unlike any other

on the globe. Cappadocia is a semi-arid region that is covered with a deep layer of soft

rock called "tufa," composed of volcanic lava and ash deposited millions of

years ago by four now extinct volcanoes. Wind and water have created a heavily eroded

moonlike terrain where bits of hard basalt have protected the underlying tufa from

erosion, leaving towers that often still wear their basaltic caps. These are the

"fairy chimneys" of Cappadocia.

Beginning in the first century, Christians hiding from the Romans carved homes and churches within the tufa towers and also underground. Many of the churches were lavishly decorated with frescoes, some exquisite, some primitive. Later, Byzantine Christians hid in the tufa sanctuaries from Muslims. Some of the rock dwellings were occupied as late as the early twentieth century. Indeed some hollowed towers are still used as shops, restaurants and stables.

One of the most important sites in Cappadocia is the open air museum at Göreme. This is a cluster of small churches carved within the tufa chimneys. Some contain frescoes, and like most early churches, graves. Some of the churches must be entered by ladders that would not pass most safety standards. One particularly notable church near the parking lot has a high ceiling, carved columns and well-preserved frescoes. Take a flashlight for viewing the frescoes. Flash photography is not permitted in most of the churches.

The next day we visited Kaymakli, another site that should not be missed. This is one of the most impressive of approximately two hundred underground cities in the region. Carved from the tufa substrata, some of the caverns were occupied as early as four centuries ago by the Hittites. Most, like Kaymakli, were constructed by Christians from 3rd century A.D. as refuges from Persian oppressors.

Entrance to the multi-story underground Kaymakli is only with an authorized guide. The

descending route is marked with red a rrows, ascending with blue arrows. We were led

through rooms for dwelling, storage, meeting, wine-making, cooking and eating,

worshipping, stabling animals, every imaginable space required by a living community. All,

that is, except toilets. None have been definitely found.

rrows, ascending with blue arrows. We were led

through rooms for dwelling, storage, meeting, wine-making, cooking and eating,

worshipping, stabling animals, every imaginable space required by a living community. All,

that is, except toilets. None have been definitely found.

Take great care in the underground visit. No one who is the least claustrophobic should attempt it. People who are overweight or not supple should consider carefully since tunnels are narrow and low. Stay with your leader. The city was a refuge from enemies, and the occupants devised means to thwart and punish invaders, such as deep shafts into which intruders might fall. Not all of the tunnels are marked or known. The spaces are lighted, but take a flashlight for emergencies and to illuminate dark corners. Air shafts pierce the surface, but they were hidden above and provide no illumination.

Our hotel in Cappadocia was the Kapadokya Lodge. Ahmet called it the best hotel in the region, if not in all of Turkey. It is indeed plush but without the aura of luxury, which I find unpleasant. The rooms are comfortable and well appointed. The pool and gardens are attractive, the lounge inviting, and the dining room is light and airy.

From Cappadocia we drove most of a day to Konya. En route we were given a longer than usual rest stop where we bought refreshments, the bus was washed, and we changed into long pants. Konya, a religiously conservative city, is the center of the Mevlevi Order of Sufis, called "whirling dervishes" by westerners for their ecstatic revolving dance. The meditative whirling dance, or "sema," is said to symbolize the rotation of the universe around God. The dancer turns with arms extended, the right palm turned heavenward, the left hand turned to the ground, receiving heavenly energy with the right hand and transmitting it to the earth with the left.

Founded in the late 13th century, the sect is based on the writings of

Mevlâna Celeddin-I-Rumi, the Persian poet. The sect was suppressed by the new Turkish republic in 1925, and the dance virtually disappeared. Since 1954, Ankara has permitted

the dance to be performed for tourists in Konya in December on the anniversary of

Rumi’s death.

republic in 1925, and the dance virtually disappeared. Since 1954, Ankara has permitted

the dance to be performed for tourists in Konya in December on the anniversary of

Rumi’s death.

We visited the Mevlâna Müzesi, a monastery, museum, shrine and monument to Rumi. It is easily identified by its turquoise fluted dome. Here are the turban-topped sarcophagi of Rumi, some relatives, abbots and disciples. Turks, who greatly outnumber foreign visitors, are obviously awed by the spectacle. Testifying to the respect in which the sect is held, many Turks visit Konya before departing on a pilgrimage to Mecca. If you appear in shorts, you will be loaned a sarong to wrap around your exposed legs. You’ll also be instructed to take off your shoes and carry them in the plastic bag provided.

Leaving Konya, we drove to the small village of Akburun where we were treated to a homestay. Hardly had we stepped from our bus when two dozen excited children crowded around us. They delighted in walking with us, holding hands, smiling and trying to make conversation. We were delighted as well. They posed happily for pictures. Returning to the bus, we were welcomed by our host family, a farming couple, their sons and daughters, in-laws and grandchildren. We gathered in an upstairs room, sitting on the floor, and found an easy friendship, with Ahmet acting as interpreter.

Dinner was served to some, including family members, sitting at table and others sitting on the floor in another room around a circular table. The women of the house were absent, cooking downstairs, and the sons served. After dinner, we returned to the meeting room where we sat on the floor and were served Turkish tea. Later, the men in our group were bedded down on the floor in two rooms, the women in another room. The thirteen of us shared one w.c., surprisingly without any major problems. A refreshing rain fell softly during the night.

Carol and I and some others went out at daybreak to walk around the village. It was

still and quiet. Uniformed middle school children waited at a bus stop. Some adults also

waited, probably bound for work in a town some miles away. We walked down to the lake and watched the sun trying

to break through the heavy overcast above the mountains on the other side. But rain

threatened, and we returned to the house for breakfast.

town some miles away. We walked down to the lake and watched the sun trying

to break through the heavy overcast above the mountains on the other side. But rain

threatened, and we returned to the house for breakfast.

After breakfast, we visited a class in the village elementary school. I recognized some smiling faces from our arrival yesterday. The twelve students sang a song for us, a sort of Turkish "Old McDonald," and we responded with the American "Old McDonald". We got as many laughs as cheers, and we loved it. Later, the principal told us that they desperately needed an English teacher. He said that the pay is small, but they provide housing. Hmm. Carol is a retired English teacher. Hmm.

We said our goodbyes to our hosts and boarded our bus to drive through a region of cultivated fields and woods and the uplands of the rugged Taurus Mountains. We stopped for lunch at a pleasant covered terrace café overlooking the Manavgat River.

Resuming our journey, we arrived at Aspendos and thereby began our visit to another Turkey. This was the Turkey of the Greek and Roman worlds. We saw some of the most exciting and romantic extant Greek and Roman sites anywhere, better than most that I had seen in Italy and Greece.

According to legend, Aspendos was founded by the Greek victors following the Trojan War

in the 12th century B.C. There has been little excavation in the area, so there is little visible evidence of the

town’s Hellenistic period. Aspendos is best known for its magnificent Roman theater.

Built in the 2nd century A.D., the structure is one of the best examples of the

genius of Roman architecture. This is the best preserved Roman theater in Turkey, perhaps

in all of Asia, thanks in part to the Seljuks who restored it in the 12th

century and used it variously as a palace, caravansary and mosque. It was restored again

in the 20th century at the command of Atatürk.

According to legend, Aspendos was founded by the Greek victors following the Trojan War

in the 12th century B.C. There has been little excavation in the area, so there is little visible evidence of the

town’s Hellenistic period. Aspendos is best known for its magnificent Roman theater.

Built in the 2nd century A.D., the structure is one of the best examples of the

genius of Roman architecture. This is the best preserved Roman theater in Turkey, perhaps

in all of Asia, thanks in part to the Seljuks who restored it in the 12th

century and used it variously as a palace, caravansary and mosque. It was restored again

in the 20th century at the command of Atatürk.

The theater may be the only one anywhere with an original intact wall behind the stage. The complete covered gallery at the top is unique in surviving theaters. With a capacity of 20,000, the theater, which has wonderful acoustics, is still used today for concerts and plays. Also worth seeing in Aspendos is the 2nd century Roman aqueduct and the exquisite stone bridge built by the Seljuks in the 13th century on the foundations of a 2nd century Roman bridge.

We drove southward to an even more ancient site at Perge. Dating from 1000 B.C., the port city flourished during the Hellenistic and Roman eras, reaching its peak in the 2nd century A.D. when its population was 100,000. The extensive remains of the town show evidence of its culture and commerce, revealing a prosperous, comfortable lifestyle. St. Paul preached here in the 1st century and established a Christian community.

One can spend the better part of a morning, if not an entire day, here. The theater is built on a hillside, reflecting its Greek origins—Roman theaters, which made extensive use of arches, did not depend on a hillside location—but it has been closed to the public for quite some time for restoration. Nearby is the Roman stadium, constructed in the 2nd century A.D., with a capacity of 12,000. Enough remains to excite the imagination. It was originally used for events featuring athletes and gladiators, but it was later altered to permit wild animal spectacles.

We entered the city through the impressive 4th century oval Roman gate. Straight ahead, the two round gate towers, dating from the 3rd century B.C., were part of the defensive wall of the Hellenistic city. Passing through the towers, we walked the colonnaded main street of Perge. Stretching from the gates to the acropolis three hundred yards away, the sixty-foot wide street still shows outlines of the shops that had lined its route. Wheel ruts are clearly visible in the stone road surface.

The agora lies adjacent to the main street. The shops that opened onto the 4th century B.C. market square were a uniform design and size. A fountain stood in the center of the square. It took little imagination to picture citizens strolling about, standing under colorful awnings, examining goods and gossiping, two idlers sitting on low stone benches on each side of a stone table with a game etched on its surface.

Opposite the Agora is a structure that must have been a busy place in ancient Perge. All of the features of the large Roman bath are visible: fountains; a dressing room and an exercise room; hot, warm, and cold water rooms; spaces where the fires were stoked and the room where water was heated. Remnants of colorful floor and wall tiles hint at the rich decoration of the interior.

Leaving Perge, we drove to Antalya. This modern city is Turkey’s leading tourist destination on the Mediterranean coast. It has much to offer, a pretty setting on a wide bay, backed by the high Taurus Mountains, snow-capped until summer, and forests with picturesque valleys and waterfalls. A stroll in the narrow, winding lanes of the well-preserved Old Quarter is most rewarding.

Tracing its origins to the 2nd century B.C or the 2nd century A.D., depending on which account one accepts, Antalya fell successively under the control of Romans, Seljuks, Ottomans, Turks—and Germans who come every year to the turquoise coast by the multitudes. In some areas, signage is bilingual, Turkish and German. More will come and stay longer now that Turkey has recently made it legal for foreigners to own land.

The Archaeological Museum is a must-see. This is one of the richest, most exciting museums I have seen anywhere. Here are displayed ancient treasures that were brought to Antalya from sites throughout the region, but chiefly from Perge. Exhibits include prehistoric relics, Greek and Roman sculpture, sarcophagi, friezes, coins, and mosaics and other artifacts of the Ottoman period.

Our hotel in Antalya was a winner. The

Aspen Hotel, located in the protected Kaleiçi district, had been an Ottoman residence

before conversion. Rooms are located on walks and passageways around an enclosed

courtyard. The passageway outside our room had a nice view of the harbor. There is a small

pool and terrace bar in the courtyard. The pool was most refreshing after a day of

touring. A stair leads down to the outside dining area. Take note if you are swimming at

meal time. Diners look into a wall of glass that is the side of the pool.

Our hotel in Antalya was a winner. The

Aspen Hotel, located in the protected Kaleiçi district, had been an Ottoman residence

before conversion. Rooms are located on walks and passageways around an enclosed

courtyard. The passageway outside our room had a nice view of the harbor. There is a small

pool and terrace bar in the courtyard. The pool was most refreshing after a day of

touring. A stair leads down to the outside dining area. Take note if you are swimming at

meal time. Diners look into a wall of glass that is the side of the pool.

There was time in Antalya for some shopping, checking email at an internet café--300,000 lira (45˘) for half an hour--and getting a refill at an ATM. Be advised to get someone at your hotel to mark on a map the locations of the places you wish to visit. I did not. I found few English speakers on the street and in the shops, and those who could understand my questions didn’t know what I was looking for: ATM, cash machine, cash point, etc., and internet café. A couple of men clearly thought I was panhandling. Carol and I wasted a couple of hours searching.

We had to leave Antalya much too soon, but we were rewarded after a two-hour bus ride.

Ancient Phaselis is among the most impressive sites in Turkey. Founded in the 7th

century B.C. by colonists from Rhodes, the town was dominated  successively by Persia, Athens and Rome. This was a small town, located on a

peninsula, shaded by cool pines.

successively by Persia, Athens and Rome. This was a small town, located on a

peninsula, shaded by cool pines.

The first view of Phaselis is the graceful, well-preserved stone aqueduct which supplied the town with water. We walked along the beach and then down the lane, paved with stone slabs, that stretched from the pebble beach on one side of the peninsula to a pretty bay on the other side. The shady road is lined with ruined shops, small agoras and baths. Ruins are Roman and Byzantine for the most part, but Greek inscriptions also suggest an earlier presence. Just off the road behind the shops, the exquisite little theater, built on a gently sloping hill, seated only 1,500. The site lies within the borders of a national park, ensuring its preservation.

We drove inland through red pine forests to the village of Ulupinar where we had lunch at a restaurant on a trout farm. The cool shade under pines and awnings was most welcome. All in our party had fresh trout except Carol. She likes trout, but she was influenced by her glance at the plates of nearby diners. Heads and tails of the fish hung over the side of the plates. She had a spicy vegetable-beef stew instead, which she pronounced delicious.

Continuing our drive along the coast, we visited ancient Olympos. This required a walk along a beach, popular with sun and sea bathers, and around a rocky point to the site. Dating from before the 2nd century B.C., the ancient city was built on both sides of a stream. The ruins, mostly Roman and Byzantine, lie in heavy vegetation. Only about 10% of the city has been excavated. There is a feeling of mystery and romance about the place. The unusual nature of the site is evident also in the commercial presence, hardly a village, at the parking place where we were dropped off. There is a bar, a small restaurant, volleyball and ping pong, and a general store. The sparse accommodation is in inexpensive tree house pensions. The place is popular with backpackers.

A short drive down the coast brought us to the trailhead for the climb to the eternal flames of the Chimaera. The flames emerging from a rocky hillside were thought in ancient times to be the breath of a mythical creature, the Chimaera, part goat, part serpent, and part lion. Read the fable of Bellerophon and the Chimaera for the whole story. Modern geologists add that the beast’s breath is likely methane gas. Locals say that the spectacle of the Chimaera is best seen at night. Good luck. The trail was hard enough for me in broad daylight.

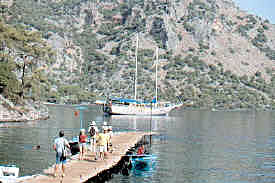

We returned to our bus for an hour’s drive to Finike where we boarded our gulet. The gulet experience was one of the principal reasons for my booking this tour. I had read glowing accounts written by people who had sailed in gulets and corresponded with them. My expectations were high. I braced myself for disappointment.

On the first sight of our

gulet, my fears evaporated. It was a

sleek, almost new, boat built of teak and oak on the same lines as generations of coastal

sailers that dated from the Roman era. We boarded, and I was delighted. Champagne was

poured, and we met the crew of four. Then we drew lots for cabin assignments. Carol drew

the number for one of two cabins in the stern. The cabin was roomy, with a double bed, a

small dresser and a surprisingly large head with a separate shower enclosure. We had two

portholes and a transom window in the stern. When we were underway, the churning water was

hardly three feet below the open window.

On the first sight of our

gulet, my fears evaporated. It was a

sleek, almost new, boat built of teak and oak on the same lines as generations of coastal

sailers that dated from the Roman era. We boarded, and I was delighted. Champagne was

poured, and we met the crew of four. Then we drew lots for cabin assignments. Carol drew

the number for one of two cabins in the stern. The cabin was roomy, with a double bed, a

small dresser and a surprisingly large head with a separate shower enclosure. We had two

portholes and a transom window in the stern. When we were underway, the churning water was

hardly three feet below the open window.

For the next six days, we sailed along the beautiful

Turquoise Coast. We enjoyed cruising, kicking back on the deep cushioned seats on the

stern with drinks and books, or simply staring at the horizon. Meals were taken topside on

the stern. Fare was delicious, varied, and ample. The cook was a favorite crew member,

with a good sense of humor in spite of the language barrier. The bar was in the sitting

room below deck, convenient to cabins and the topside dining-lounging area on the stern.

For the next six days, we sailed along the beautiful

Turquoise Coast. We enjoyed cruising, kicking back on the deep cushioned seats on the

stern with drinks and books, or simply staring at the horizon. Meals were taken topside on

the stern. Fare was delicious, varied, and ample. The cook was a favorite crew member,

with a good sense of humor in spite of the language barrier. The bar was in the sitting

room below deck, convenient to cabins and the topside dining-lounging area on the stern.

We landed once or twice a day to visit a village or a beach, an ancient site or to hike inland. After breakfast on our second day aboard, we motored to Andriake where we found our bus for the short drive to Kale, or Demre to the locals, where we visited ancient Myra. This important city in the Lycian League was visited by Roman emperors and by St. Paul en route to Rome. Dating from at least the 4th century B.C., the city grew in wealth and importance during the Roman era and reached its peak in the Byzantine period. Like other cities on the Mediterranean coast, it declined under the Arab onslaught of the 7th century.

The remnants of Lycian Myra are imposing. The striking

Roman theater features cavernous vaulted galleries that supported seating on semi-circular

marble tiers for 10,000 spectators. On the steep hillside adjacent, tombs cut from the

living rock in the 5th century B.C. are decorated with columns and arches. My

mind raced as I stood at the foot of the cliff face.

marble tiers for 10,000 spectators. On the steep hillside adjacent, tombs cut from the

living rock in the 5th century B.C. are decorated with columns and arches. My

mind raced as I stood at the foot of the cliff face.

Kale/Demre is also famous for its association with St. Nicholas. Born in the region about 300 A.D., St. Nicholas was revered for his charitable works, his concern and care of the poor and orphans, and his role in the expansion of Christianity. He is buried in the church at Demre that bears his name. The real St. Nicholas is thought by many to be the prototype of today’s Santa Claus. I was pleasantly surprised to find no Santa Claus souvenirs in the shops near the church.

Alas, St. Nicholas is no more. The Vatican stripped him of sainthood in 1969, declaring that the tales of his miracles and other good works were only that.

Back at the gulet, we had a refreshing swim off the side of the boat. Lunch was a treat, as usual: moussaka, fluffy rice, yogurt, french fries, a salad of tomatoes, cucumbers, onions and greens, and fruit—apples, peaches, grapes, kiwi. After a short siesta, the hikers went ashore at Gokkaya for a walk.

Leaving the lightly wooded shoreline, we crossed a rocky flat to a brushy hillside

where we walked on the broken pavement of a Lycian road. I pondered those other travelers

on this same road. We passed a sleepy village that had been vibrant and populous when the

road was smooth. Climbing again, we topped a rise and saw the sea. Our

gulet, which had sailed ahead to meet us, lay at anchor in

the bay below. On the plateau where we stood, huge Lycian tombs, carved from single stones

and topped with steeply curved tops, gave the appearance of upturned boats.

which had sailed ahead to meet us, lay at anchor in

the bay below. On the plateau where we stood, huge Lycian tombs, carved from single stones

and topped with steeply curved tops, gave the appearance of upturned boats.

We climbed higher still to Simena Castle which dominated the bay and the ancient village of Simena on Kalekoy cove below. The red flag of Turkey flew from the topmost battlement. A tiny theater with but seven tiers seating only 150 lies within the castle walls. It was clear by this time that the theater was one of the paramount necessities in the Greek and Roman worlds. We made our way down the steep hillside to the water’s edge where the small boat awaited us. Back on the gulet, we poured drinks and relaxed on the stern. What a day!

Those who had remained on board were treated with a pleasant cruise around the point. Before they dropped anchor, a couple of rowboats moved away from the village pier and headed for the gulet. The "merchants" were children. "Want to buy a scarf? Maybe? Maybe later?" "Why not?" Silence. This was probably the extent of their English. A pretty little girl of seven, who had rowed alone to the gulet, could not be resisted and found buyers for her bracelets.

We motored down the coast and anchored near Aperlea, an ancient town that had partially submerged during an earthquake. The outlines of buildings and fallen columns were clearly visible to snorkelers at about ten to twenty feet down. The water here appeared to be especially salty. It felt like one was lying on the water rather than in it.

Next day we docked at Kas, a busy picturesque seaside village that caters to the

tourist trade. Its cobblestone lanes are lined with old bay-windowed shops selling rugs,

rugs, rugs and other things that visitors might wish to take home with them. A huge Lycian

sarcophagus, the emblem of Kas, sits at the top of

one lane. Small the town may be, but it supported two internet cafes as well as reasonably

priced accommodation, restaurants and bars.

top of

one lane. Small the town may be, but it supported two internet cafes as well as reasonably

priced accommodation, restaurants and bars.

While Carol strolled about the shops, I walked outside town to the exquisite little Hellenistic theater. It is all by itself, with no hint of a commercial presence, not even a single vendor. The patrons had a magnificent view of the sea. How pleasantly distracting that must have been. I sat on a tier at the top, watching a lone sailboat below cutting through the blue waters. Following the hot walk back into the village, I was happy to sit down in the shade with a large glass of refreshing freshly-squeezed orange juice.

Underway again, Ahmet fished over the side. No luck. We kicked back on our cushions on the stern, reading and enjoying tea and cakes and the sea. We dropped anchor near Gemile Island. Eight of us hiked to the top of the island, making our way through the ruins of ancient churches and a 6th century Byzantine monastery. At the peak, we watched the setting sun and toasted its glory with red wine. On the way down, we paused to look at a beautiful recently-excavated tile floor in a monastery chapel.

We took breakfast as usual at our table on the fantail. The slanting sun made the water sparkle and illuminated the remnants of the night’s mists that lay between the layered hills. Ahmet broke the spell with a call to the small boat. We motored to the beach at Oludeniz for a wet landing, carrying our shoes. Neat rows of empty beach chairs awaited the tourists.

Our bus took us to a most melancholy site. Kayakoy was a bustling Anatolian village built on the gentle slope of a hillside until the 1920s when its Greek inhabitants were evacuated in the forced exchange of Greeks and Turks between the two countries following the Turkish war of independence. Greeks who had been born—and whose parents had been born--in Turkey were forced to move to Greece, and Turks who thought they were Greek were removed to Turkey. Now Kayakoy’s six hundred stone houses are roofless and empty. Grass grows in the paths, and roads have been lost to erosion. The only sounds were the wind and our own voices.

Back on the gulet, we easily forgot the folly of war and nationalism. We swam in the beautiful little cove, then boarded for a sumptuous lunch of stuffed eggplant, zucchini and peppers, fried carrots, eggplant and potatoes, a curly pasta with meat, and for dessert baklava without honey, watermelon and honeydew melon. An ice cream vendor pulled his boat alongside and found eager buyers. We fetched our books and journals and found our spots on the fantail cushions or at the table, reading, writing and sleeping.

Our reverie was broken by the appearance of a sleek sailboat with three couples aboard who proceeded to try to anchor. They entertained us for an hour as they maneuvered near an anchored boat, backing and moving forward, dropped a bow anchor, sent a small boat to shore to tie up to a tree, unfortunately sending two men who could not agree on where to tie up as the sailboat drifted toward the adjacent anchored boat. Our crew were all on deck, enjoying the spectacle. The captain thought it hilarious, but his professional concern prevailed, and he motored over in our zodiac to help. Or did he just want to get a closer view of the topless woman on deck? In any event, he helped the obviously inexperienced tourists anchor properly.

The next morning the hikers crossed the peninsula while the gulet motored around the point to a bay on the other side. We walked up a Lycian path paved with marble slabs to the spine of the ridge. There we saw a fascinating ruin. This was the Greco-Roman town of Lydea. The site sees few visitors since no modern road comes here. There are scattered remains, the walls of a church, a house, perhaps a bath, a hint of a theater. A hint because the site is completely unexcavated. What architectural and cultural treasures could lie just beneath the surface! How fascinating it would be to be here when the first spade is turned. Leaving reluctantly, we walked through a cool pine forest down a steep path to the cove where our gulet lay at anchor.

Before boarding, we stopped near the small pier to see the Baths of Cleopatra,

reportedly given to her by Mark Antony. In fact, or rather in legend, Antony  gave her the whole of the Turquoise Coast. If we can

believe the stories, Cleopatra bathed in as many places on this Mediterranean coast as

Washington slept in on the American Atlantic coast. We had some difficulty viewing the

baths because a filming crew was there and clearly saw us as obstacles to their work, but

they were patient and polite, and we tried to oblige them. We looked for Cleopatra in vain

then boarded the launch and returned to the gulet. A swim off the side was most

refreshing.

gave her the whole of the Turquoise Coast. If we can

believe the stories, Cleopatra bathed in as many places on this Mediterranean coast as

Washington slept in on the American Atlantic coast. We had some difficulty viewing the

baths because a filming crew was there and clearly saw us as obstacles to their work, but

they were patient and polite, and we tried to oblige them. We looked for Cleopatra in vain

then boarded the launch and returned to the gulet. A swim off the side was most

refreshing.

After lunch, we lifted anchor and sailed away. Literally. The gulet is rigged for sail, but it is a motor sailer with the emphasis on motor. The sails are rarely unfurled. But on this day, the crew raised sail. Not without some difficulty. It was obvious that this was not a usual procedure. After sailing for some minutes in a stiffening breeze, the crew tried to drop the sails. The mainsail would not come down. Ultimately, they had to raise a crewman up the mainmast by a jury rig that scared me to death. He was sitting in a rope loop, with nothing holding him but his own hand. At the top, he jiggled the ring, but the sail would not drop. They sent up what looked like a kitchen butcher knife. While holding himself with an arm around the line he was sitting in, he sawed at something. After some anxious minutes the sail began to slide down the mast. The crewman came down the mast with the knife in his back pocket. Through all this, I was torn between going below to avoid seeing a disaster and staying on deck to help. Instead I did neither and expected the worst. We all breathed a great sigh and applauded when he reached the deck. The gulet, or at least this gulet, is not a sailboat.

We tied up that evening in a cove that was partially protected from the wind. As usual, we dropped the bow anchor and backed toward the beach as a crewman went ashore in the launch to tie the stern line to a tree or rock. This time he tied the line to a tree about six inches in diameter, a mere sapling. I was sure we would uproot the tree in the wind and drift sideways onto the rocks, but I decided that the captain had done this before and I would not worry.

At dawn, I came on deck to see that we were still securely tied at both ends. The sea was smooth as glass. During breakfast, a small river boat arrived to transport us on the morning’s excursion. We cruised up the meandering Dalyan River, moving through the reeds and cattails. We saw no giant turtles that are reputed to be here, but we did see some colorful birds. We docked and walked to the site of the Carian town of Caunus. We walked through the remains of the theater, temples, baths, and other buildings dating from the 9th and 10th centuries B.C. A new excavation had just uncovered a perfectly-preserved cobblestoned street surface. Caunus had once been on the river, but silt had long ago formed the meadow in front of the town. A crusaders’ castle looked down on the town site from the crest of an nearby hill.

Returning to our launch, we motored further up the river, passing Carian tombs carved into the rock face of the riverside cliffs. We put in at Dalyan, a busy, clean little town where we had lunch in a local restaurant that opened onto the street. The shade and breeze was pleasant, and the fare good. A nearby internet café was tempting, but there was no time for correspondence.

Carol found time nevertheless for some hurried shopping. She bought a copper measuring cup from a pleasant vendor and laid her payment on the counter. The woman told her that she was her first customer of the day and swept the bills to the floor. Carol didn’t know what to make of this. The woman then insisted that Carol take some candies as a gift. Another shopkeeper explained that sweeping the money to the floor was a Jewish custom that was practiced by some Turks in the town.

We soon boarded the launch and returned to our gulet. We motored to a cove where we tied up for the night. The lights and sounds of Marmaris across the bay told us that our gulet experience was nearing an end.

After breakfast the next day, we cruised across the bay to the Marmaris harbor. Just before docking, a small hydrofoil ferry passed us at full speed, slowed, lowered and drifted to the dock. After tying up, we said goodbye to the crew and boarded our bus. There was enough free time before leaving Marmaris to wander about the market and try to avoid buying. No luck. Tour members arrived at the bus later with purchases in hand. I bought a white ball cap emblazoned with the Turkish crescent and star symbol and the word "Türkiye" in embroidered colors. I buy little but ball caps and T-shirts on trips, and I was disappointed to find only T-shirts with printed American and British brand names or English writing.

Bound now for Kusadasi, we stopped for lunch at a hilltop restaurant. We sat at shaded tables on the terrace, overlooking the sea. A woman sat under an arbor nearby, making Gozleme, a delicious round flat bread. The weather was quite warm, but the lunch was appetizing, topped off with the usual good watermelon, honey dew melon and fresh peaches, and the view was spectacular. One last look and we were on our way, driving in our air-conditioned bus past cotton fields and olive and fig orchards.

Kusadasi is well-known as a resort for those whose interest in Turkey is primarily, or solely, a visit to nearby Ephesus. As the bus neared the town, I was dismayed at the huge sterile tourist hotels that we passed. Happily, we passed them all and pulled up at the Kismet Hotel. It is perfectly sited on a high peninsula with a view of the harbor in the front and the bay at the back. There is a concrete quay at the back for sunning and swimming. I went in the water twice, a bit cool, but so refreshing.

Our room was on the ground floor. The outside door opened to a small private terrace with a low wall which looked out on the lawn and gardens. Our group gathered later at pine-shaded benches on the lawn for drinks. The pretty harbor below was filled with pleasure craft of all sorts and sizes, mostly sailboats. Dinner later was sumptuous but informal. Indeed the Kismet, like the Kapadokya Lodge in Cappadocia, was posh without being stuffy.

The next morning, I stepped out on our terrace and grimaced. The harbor, which had been so appealing last evening with its forest of masts and colorful small boats, was now filled with what appeared to be a fallen skyscraper. The liner was backing to the pier, a process that continued for quite some time. Ahmet had anticipated the arrival of the cruise ship, and we got an early start for Ephesus to try to beat the exodus that would begin soon after the docking.

Ephesus is the largest and best-preserved Greco-Roman ancient site in Turkey. Its beginnings precede 1200 B.C. The town at various times fell under control of Ionians, Cimmerians, Lydians and Persians. Alexander the Great ruled for a time. Eventually the Romans won sovereignty. In the 3rd century AD, the Goths ravaged the city, and it never recovered.

After an introductory comment, Ahmet conducted us to the principal sites. There is little remaining of the extensive State Agora except foundations. Roman ceramic water pipes lie partially exposed and unprotected on the surface of the market. Proceeding down the stone-paved road, we saw the Odeion, once a covered theater-like structure seating 1500, where the advisory council met. Statues of Emperor Augustus and his wife Livia, found in the adjacent Basilica, are displayed in the Museum of Ephesus in Selçuk. Two many-breasted statues of Artemis found in the Prytaneion, a municipal building which housed the town’s executive council, are also in the museum. We paused at the high arch of the Fountain of Pollio and the two large columns of the Temple of Domitian. A relief of Nike, Goddess of Victory, stands at the roadside.

Passing through the monumental Hercules Gate, we entered the remarkably-preserved Curetes Street. Not all the paving is original. It was repaired in the 4th century A.D. It is rumored that authorities are considering a plan that will eliminate walking on the street surface.

The street is lined with columns and statues of important persons. The Fountain of Trajan and the Temple of Hadrian were dedicated to those worthies. Two statues of Dionysos found at the former are displayed at the Museum of Ephesus. Of more mundane use were the three-storied Scholastika Baths, an important gathering place, and the public latrine. The marble toilet seats are side by side with no partitions. Admittance was restricted to men only. Even in ancient times, women had problems with too few toilets.

On the other side of the street, houses for the rich were built on the slope of the hill. Two houses have been restored and, while usually open for viewing, we were unlucky and they were not accessible. Plans call for more restoration and public viewing. Some furnishings and murals from the houses are displayed at the Archaeological Museum at Selçuk.

Another edifice of practical use was the town brothel, prominently located across from the imposing Library of Celsus. Dating from the 2d century A.D., the brothel’s interior shows remains of its frescoes and marble and mosaic floors. The resident well-endowed statue of God Bess is displayed at the Museum of Ephesus.

The two-storied Library of Celsus, the showpiece of Ephesus, stands at the bottom of Curates Street. Built in the 2d century A.D., it is not a library at all, but a monumental tomb for Julius Celsus Polemaenus, a governor of Ephesus. Statues that stand in niches of the façade were meant to represent the various virtues of Celsus. Unfortunately some Austrian archaeologists who excavated here in the early 20th century were able to transport four statues and some valuable high relief carvings to the Kunsthistorische Museum in Vienna.

Just off the courtyard in front of the library, the well-preserved marble Gate of Mazaeus and Mithridates provides access to the Mercantile Agora. Mazeus and Mithridates were freed from slavery by Emperor Augustus. In gratitude, the two freeman constructed this gate in the 3rd century B.C. in Augustus’s honor. The agora’s colonnaded square was the center for commerce in the town. Covered shops lined the perimeter. Little remains today but some columns.

Continuing, we walked down Marble Street which runs from the Library of Celsus to the Great Theater. Probably the first outdoor advertisement is carved in the stone pavement. It depicted a woman and a bare foot pointed toward the brothel. If your foot did not at least cover the carved foot, then you were not sufficiently aged or properly equipped to go to the brothel.

The Hellenistic theater is the largest in Turkey, accommodating 24,000 seated and 1,000 standing spectators. Of the original triple-storied stage, only the lower survives. Built in the 3rd century B.C., patrons witnessed plays, gladiatorial combats, and animal fights. Legend says that St. Paul preached here. Twentieth-century patrons have enjoyed concerts in the theater, but since a performance of Sting resulted in riots, rock concerts have been barred.

Harbor Street runs from the theater to what was once the harbor. Now the street ends at the meadow that was formed by hundred of years of silting. The broad colonnaded roadway was originally lined with shops. We passed the scant remains of the Harbor Gymnasium and Baths, then paused for a last look at the lower town. The theater is particularly striking from this viewpoint. Leaving Ephesus, there was time to buy refreshments and stroll a few minutes through the inevitable rug and curio shops before boarding our bus.

After a pleasant lunch high in the hills, we visited the 6th century Basilica of St. John where he is buried. The church was constructed largely of stone removed from Ephesus. The 12th century Jesus Christ mosque is nearby. In a field below the mosque stands the sole remnant of one of the seven wonders of the ancient world, the Temple of Artemis. Towering over these three holy places is a 12th century crusaders’ castle. A rich cultural mix indeed.

It had been a long, tiring, thoroughly enjoyable and rewarding day, and we were glad to

return to our hotel. After a refreshing swim and shower, we gathered on the lawn for

respite and drinks. I had a "Kismet," though I still could not comprehend paying

3,750,000 for a drink. The shade was welcome, the harbor was tranquil again, and the

conversation was most acceptable.

It had been a long, tiring, thoroughly enjoyable and rewarding day, and we were glad to

return to our hotel. After a refreshing swim and shower, we gathered on the lawn for

respite and drinks. I had a "Kismet," though I still could not comprehend paying

3,750,000 for a drink. The shade was welcome, the harbor was tranquil again, and the

conversation was most acceptable.

After breakfast the next day, we motored to Selçuk to visit the museum where the most important portable artifacts from Ephesus are displayed. It should not be missed.

Following another pleasant lunch in a restaurant with a covered patio, we drove into the mountains where we had good views of Ephesus and the surrounding countryside. We visited the "House of the Virgin Mary," the site where legend says Mary lived following Jesus’s crucifixion. A small chapel marks the spot thought to be the site of Mary’s house. This is a popular tourist and pilgrimage site, and the crowds are formidable. Unless you are devout and need to visit the site, it is not a must-see.

Now we descended to the valley, drove to Izmir where we boarded our plane for the short flight to Istanbul. Our hotel was another winner: the Armada. We had a pleasant evening, winding down and saying our goodbyes.

In fifteen years of organizing and escorting tour groups, this was among the best. The itinerary was well constructed, the tour was well led by Ahmet, and the choice of hotels and restaurants was exceptional. I enthusiastically recommend Overseas Adventure Travel for its popular Turkey tour. Contact OAT at 800-955-1925, or see their web site at http://www.oattravel.com. The only downer was the inefficiency of the air department (actually a department of Grand Circle Travel, OAT’s parent company) and the rudeness of its supervisor.

I heartily recommend the hotels selected by OAT. If you plan to travel independently, for Istanbul contact Blue House Hotel, tel. (90) 212 638 90 10, internet rate $90-125 double, otherwise $140. A good second choice is the Armada Hotel, tel. (90) 212 638 13 70, $73-109 double. In Cappadocia, Kapadokya Lodge, tel. (90) 384 213 99 45, $60-70 double. Aspen Hotel in Antalya, tel. (90) 242 247 05 90, In Kusadasi, Kismet Hotel, tel. (90) 256 618 12 90.

|

Caveat and disclaimer: This is a freelance travel article that I published some time ago. Some data, especially prices, links and contact information, may not be current. |

|

|

|

|